Survey: Expect the Fed to cut rates at least two more times over the next year

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell cautioned that the first interest rate cut in more than a decade wasn’t the start of many more. But the nation’s top economists aren’t entirely convinced.

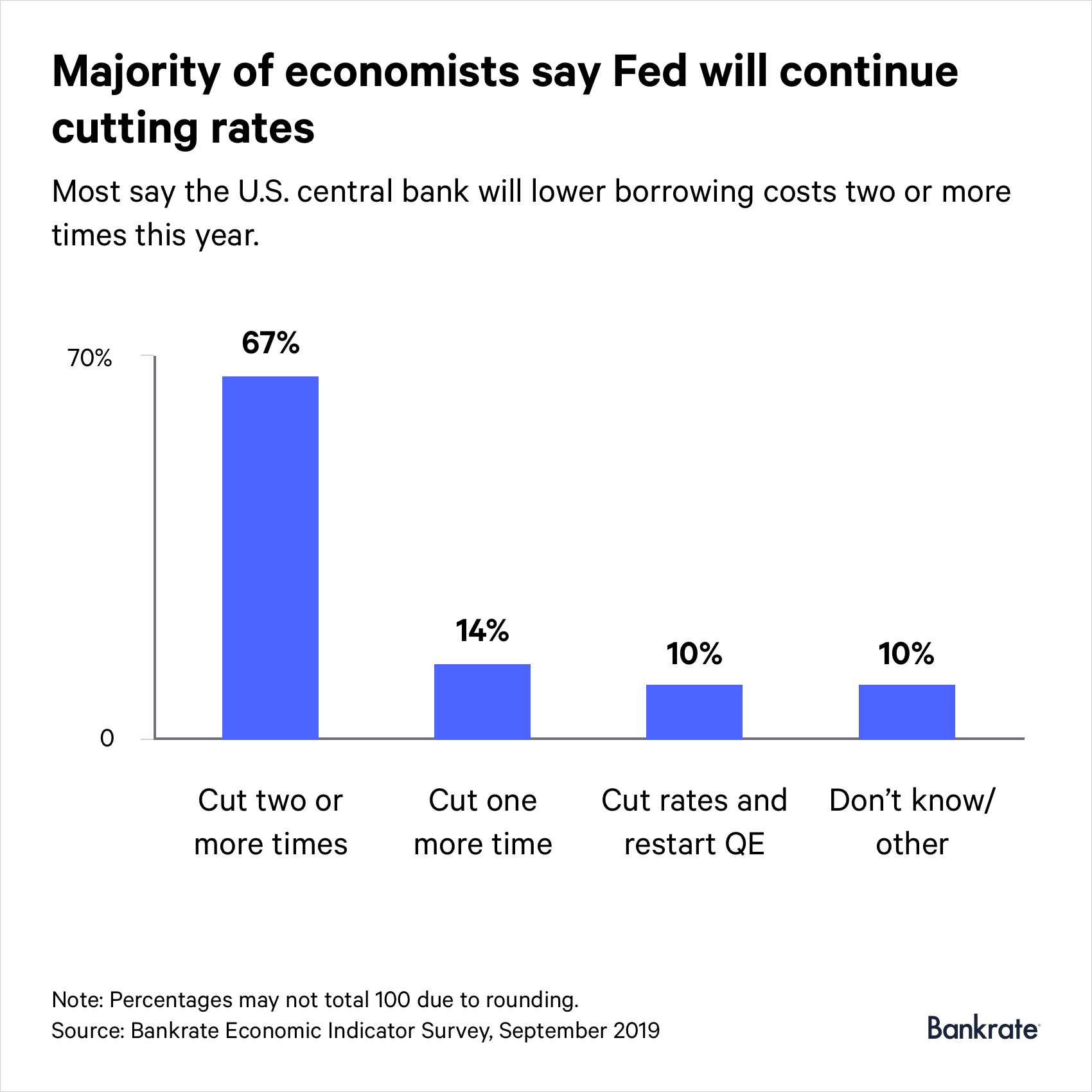

Among those experts that provided a response for Bankrate’s third-quarter Economic Indicator survey, there is universal agreement that the Fed will cut interest rates again at some point over the next year. Sixty-seven percent of respondents said the Fed will make two or more cuts, while 14 percent predicted one more and 10 percent were betting on a more drastic step: rate cuts and the return of quantitative easing (the unconventional tool that the Fed uses to push down long-term interest rates.)

That’s all because the economic outlook looks like it’s starting to deteriorate. Trade tensions between the U.S. and China escalated on August 1, after President Donald Trump threatened to hit all remaining imports from the Asian nation with duties. Meanwhile, global growth is slowing, while manufacturing activity in the U.S. is in the middle of a slump.

Ninety percent of economists in Bankrate’s survey said that the risks to the outlook were tilted toward the downside, up from 80 percent in the second quarter.

“The question we keep asking ourselves is, how many more blows can this aging business cycle take?” says Bernard Baumohl, chief global economist at the Economic Outlook Group. “We expect the economy will barely avoid a recession next year, and the consumer should get credit for that. But the escalating trade dispute, along with the havoc it has caused to supply chains and how it dampened economic growth worldwide will all be with us — at least until 2021.”

What moves will the Fed make in the year ahead?

Powell described the outlook for the U.S. economy as “favorable” during the Fed’s post-meeting press conference on July 31, saying the 25-basis-point reduction was largely meant to keep it that way at a time when a number of uncertainties are threatening the outlook.

“We’re thinking of it as essentially in the nature of a mid-cycle adjustment to policy,” Powell told journalists. “And I’m contrasting it there with the beginning — for example, the beginning of a lengthy cutting cycle.”

But officials are in a bind. Fed policymakers have a dual mandate of low unemployment and stable prices, and trade tensions could compromise those goals. The Fed, however, doesn’t know exactly how — or when — to respond when developments change so rapidly.

There are “no recent precedents to guide any policy response to the current situation,” Powell said during a speech at a Fed symposium in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, about a month following the rate decision. “Moreover, while monetary policy is a powerful tool that works to support consumer spending, business investment and public confidence, it cannot provide a settled rulebook for international trade.”

That’s exactly why economists say the Fed will likely have to alter from their current course for policy, according to Bankrate’s poll. Officials will be forced to counteract and cushion the economy from any negative trade developments.

“The Fed is in a terrible position of having to try to stave off recession in the midst of a trade war, with ballooning deficits, and many other central banks fighting their own economic woes with zero or negative interest rates,” says Amy Crew Cutts, CEO and chief economist at AC Cutts & Associates.

Some officials have already penciled in one more reduction in addition to the July 31 cut, judging from the Fed’s so-called “dot plot,” which shows officials’ forecasts for the midpoint of the federal funds rate a year from now. The U.S. central bank will refresh that chart following the conclusion of its Sept. 18 policy meeting.

But records of the Fed’s meeting in July show that many officials were divided on whether a cut was indeed necessary at that time. The Fed’s post-meeting statement showed that two officials had dissented against the consensus to cut rates — Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren and Kansas City Fed President Esther George.

Though most economists expected the Fed would cut rates at least two more times this year, they made note that the economic picture is changing rapidly, making it hard to accurately predict the Fed’s next steps.

“The situation is too volatile to predict accurately,” says Robert Frick, corporate economist at the Navy Federal Credit Union. “The two top variables include the path of the trade war (escalation or de-escalation) and the health of foreign economies.”

[READ: 4 ways savers should handle falling interest rates]

Where will the job market head in the year ahead?

But even though economists predict that the Fed is going to keep cutting rates, most are still expecting a low unemployment rate in the year ahead.

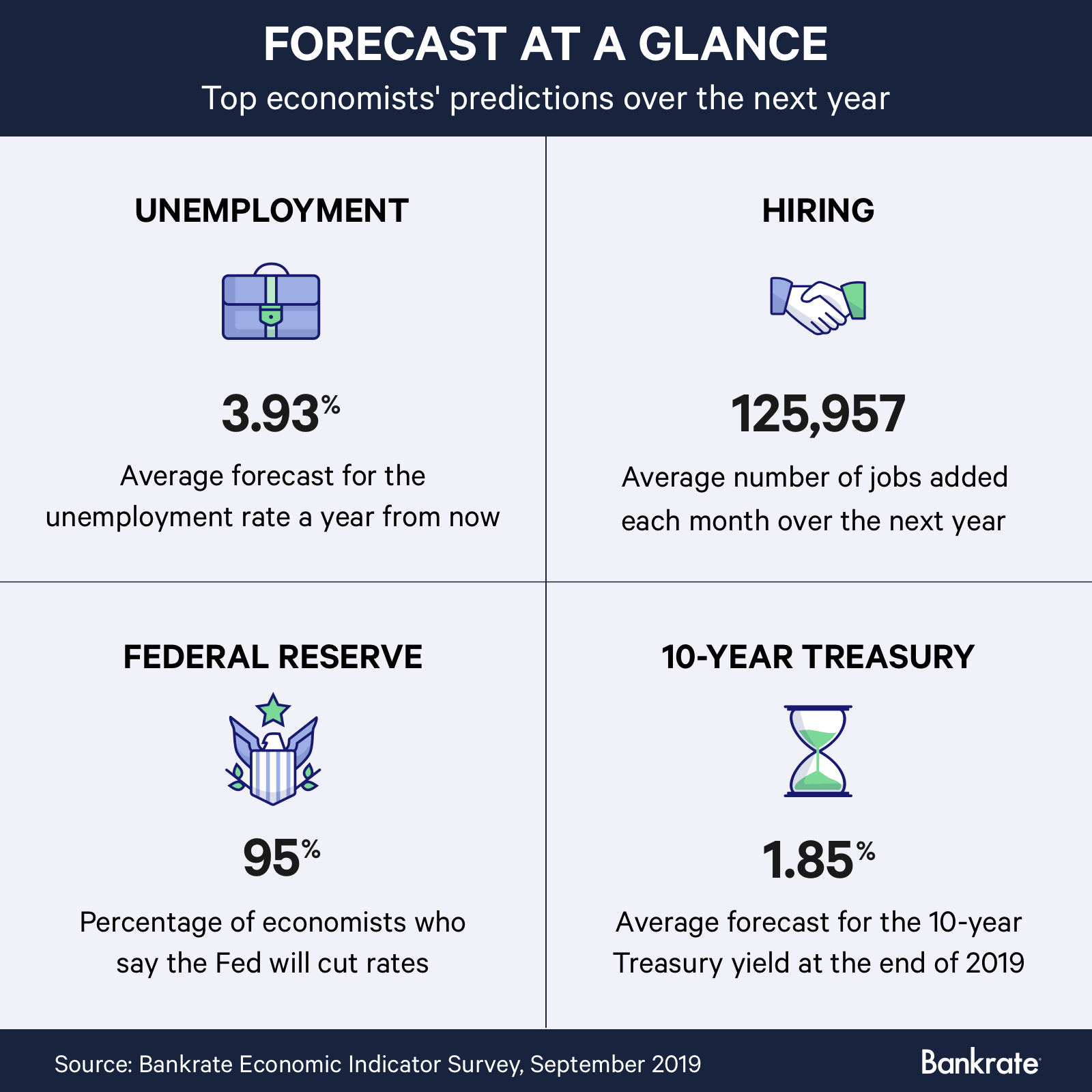

The unemployment rate was 3.7 percent in July, and it’s held under 4 percent since January 2019. Most economists expect it to stay that way, with the average forecast at 3.93 percent. Though that consensus is slightly higher than it was during the previous survey (3.88 percent), it’s still at a historic low.

“The job market is showing signs of plateauing,” says Bernard Markstein, president and chief economist at Markstein Advisors. “Employment will continue to grow, but at a slower rate, resulting in a drift upward in the unemployment rate.”

Economists are also expecting continued job creation over the next year, with the average forecast calling for a monthly increase of 126,000. That’s down by 17 percent from the last survey, which called for monthly job gains of 153,000 each week, and it’s also below the current three-month average of 140,000.

The reason? The trade war is likely going to weigh on job gains in the manufacturing and retail sectors. Meanwhile, the labor market is inching closer to full employment and growth in the U.S. is slowing, most economists said.

“Job openings remain at high levels and the unemployment rate is low,” says Mike Fratantoni, chief economist at the Mortgage Bankers Association. “But while the job market is currently very healthy, we expect that overall economic growth will slow in 2020, which will in turn cause monthly payroll growth to decline and push the unemployment rate higher.”

Where can you expect the 10-year Treasury yield to go?

The 10-year Treasury yield — a benchmark for the 30-year fixed mortgage rate — has been trading below the rate of the 3-month Treasury for more than three months. Experts say that’s a warning sign of a recession, with the inversion preceding almost every downturn in the modern era.

But on August 14, it flashed an even bigger warning sign: It started trading below the rate of the 2-year yield, a recession indicator that financial markets watch even more closely.

Economists’ forecasts for the 10-year Treasury yield in the third quarter are significantly lower than in previous survey periods — a sign that the low Treasury rates are here to stay. The average forecast calls for a 1.85 percent rate, significantly lower than the 2.67 percent consensus in the second quarter and 3.04 percent estimate in the first quarter. Nearly 20 percent are betting that the 10-year Treasury rate will fall to 1.5 percent or lower one year from now. More than half (or 52 percent), the largest cluster of agreement, say the Treasury yield will fall under 2 percent.

“While economic fundamentals remain solid in 2019, there are several downward risks looming on the horizon,” says George Ratiu, senior economist with Realtor.com. “A prolonging of the current trade war is likely to broaden its impact on US exporters and consumers through higher prices. A moderation in the pace of hiring brought about by companies’ concern over the economic outlook is likely to translate into a slowdown in wage growth, leading to softness in consumer spending. These factors could provide impetus for a slowdown toward the midpoint of 2020.”

Odds of the U.S. economy entering into a recession

Downside risks to the outlook are growing, economists said in Bankrate’s survey. Only 5 percent (one respondent) said downside risks over the next 12-18 months are tilted toward the upside, down from 20 percent in the second quarter and 24 percent in the first quarter. That means most economists are expecting risks to do more harm than good.

It also led the majority of economists in Bankrate’s survey to admit that the risks of a recession are rising. The U.S. economy has a 41 percent chance of entering into a recession by the time of the general election in November 2020, according to those polled.

“Erratic policy is raising uncertainty and anxiety, which may disrupt activity and destroy consumer and business confidence, leading to a recession,” says Robert Hughes, senior research fellow at the American Institute for Economic Research.

[READ: Watch for these 6 indicators to know when a recession could be coming]

Consumer takeaways

The U.S. economy doesn’t look like it’s going to hit a rough patch anytime soon, with economists estimating continued job gains and low unemployment. But that doesn’t mean it’s time to get complacent with your finances, says Greg McBride, CFA, Bankrate’s chief financial analyst. It’s time to make financial hay while the sun is still shining and be prepared for the downturn, whenever it inevitably arrives.

“The economy has been chugging along, with low unemployment and rising incomes. But 90 percent of the economists polled see the risks as tilted toward the downside,” McBride says. “Heed the warning and stabilize your finances now. Boost your savings, pay down and pay off high-cost debt to create some breathing room in your budget that may come in handy whenever the economy slows and your income is reduced.”

Methodology

The Third-Quarter 2019 Bankrate Economic Indicator Survey of economists was conducted August 19-26. Survey requests were emailed to economists nationwide, and responses were submitted voluntarily online. Responding were: Scott Anderson, executive vice president and chief economist, Bank of the West; Scott J. Brown, chief economist, Raymond James Financial; Ryan Sweet, director of real-time economics, Moody’s Analytics; Bernard Markstein, president and chief economist, Markstein Advisors; Robert Dietz, chief economist, National Association of Home Builders; John E Silvia, president, Dynamic Economic Strategy; Gregory Daco, chief U.S. economist, Oxford Economics; Mike Fratantoni, chief economist, Mortgage Bankers Association; Dan North, chief economist, Euler Hermes North America; Sean Snaith, director, Institute for Economic Forecasting, University of Central Florida; Yelena Maleyev, associate economist, Grant Thornton LLP; Robert Hughes, senior research fellow, American Institute for Economic Research; Bernard Baumohl, chief global economist, The Economic Outlook Group, LLC; Lawrence Yun, chief economist, National Association of Realtors; Lynn Reaser, chief economist, Point Loma Nazarene University; Joseph Brusuelas, chief economist, RSM; Bill Dunkelberg, chief economist, National Federation of Independent Businesses; Robert Frick, corporate economist, Navy Federal Credit Union; George Ratiu, senior economist, Realtor.com; Lindsey Piegza, Ph.D., managing director, Stifel Nicolaus & Co; Amy Crews Cutts, CEO & chief economist, AC Cutts & Associates LLC.

Correction: This story has been updated to reflect that the survey respondents were asked to predict rate moves by the Fed over the next year.

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.

You may also like

Mortgage rates rise despite Fed cut