Survey: 40% of top economists expect Fed to cut rates over next year

The U.S. economy has been sending mixed signals in recent days, but the nation’s top economists say there’s likely more harm than good.

Escalating trade tensions between the U.S. and China, slowing growth around the world and waning fiscal stimulus are all acting as a headwind to growth, according to the 20 leading experts polled for Bankrate’s Second-Quarter Economic Indicator survey. The majority (80 percent) of respondents say that these risks are more heavily tilted toward the downside, while just 10 percent say they’re tilted toward the upside — down from 19 percent in the prior quarter’s survey.

“Monetary policy has overly tightened, and fiscal stimulus will dry up by the end of the year,” says Dan North, chief economist at Euler Hermes North America. “Add in trade fears, decaying housing and manufacturing sectors, global weakness, and geopolitical tensions, the result is definitely more downside risk.”

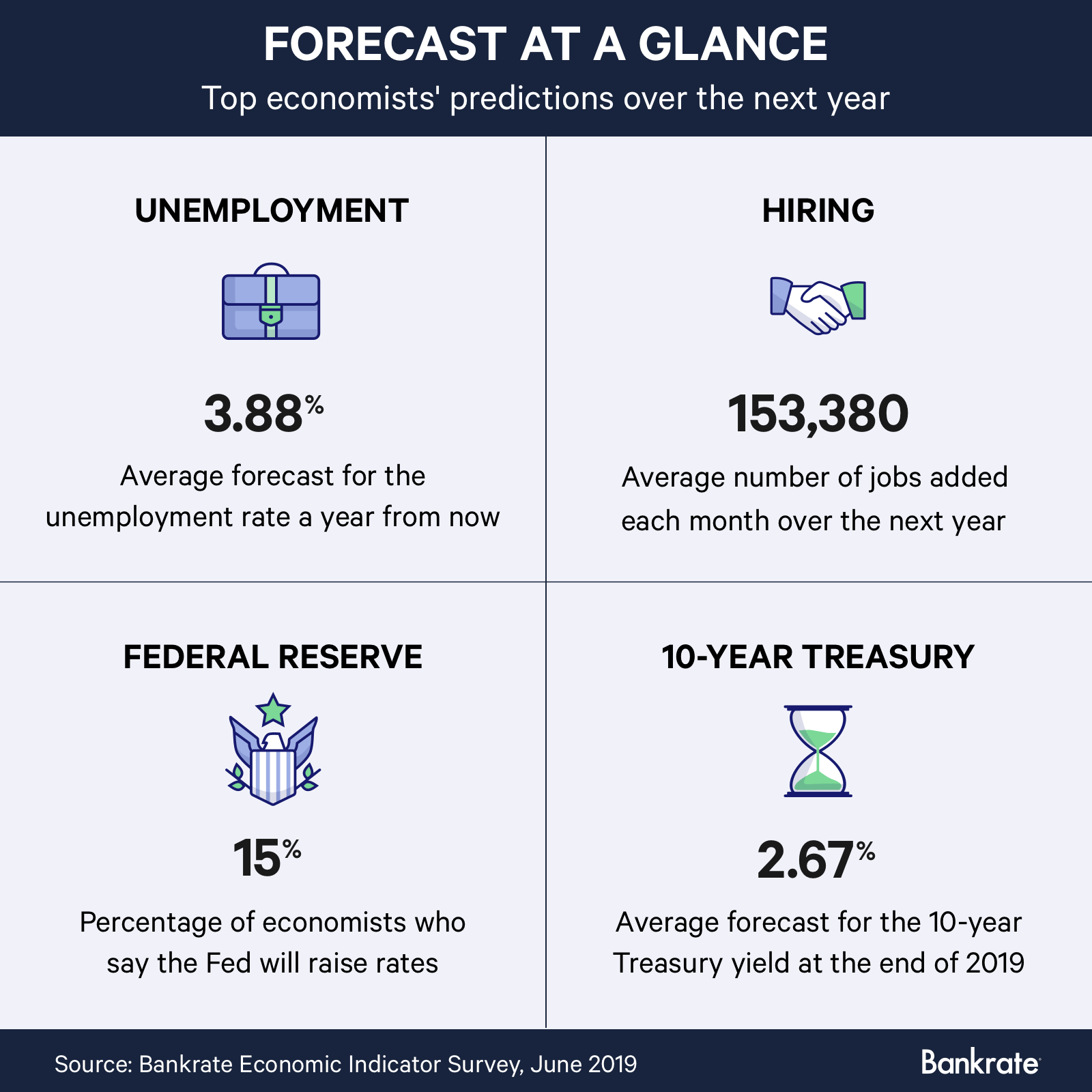

At the same time, respondents’ forecasts for the unemployment rate a year from now averaged out to 3.88 percent, the same as the preceding survey and near a half-century low. The majority of economists (90 percent) also expect the 10-year Treasury note — the benchmark for 30-year fixed mortgage rates, which has been inverted with the three-month yield for more than a week — to pick back up over the next 12 months.

“Labor market data continues to be impressive, but a slower trend in payroll gains is expected,” says Jack Kleinhenz, chief economist for the National Retail Federation. “Meanwhile, consumer spending should be [solidly] supported in the coming months, thanks to the strong jobs market, rising incomes and upbeat consumer sentiment.”

This mixed backdrop has many implications, especially for policymakers at the Federal Reserve. But for consumers, the message is clear: It’s time to make financial hay while the sun is still shining, in preparation for an economic downturn. That means paying down high-cost debt and building up your emergency savings.

What will the Federal Reserve’s next move be?

This cloudy, uncertain picture has led the Federal Reserve to re-evaluate where its interest rate policy will be heading — and so have the nation’s leading economists.

During the prior survey period, the majority of economists (65 percent) expected that the Fed would hike borrowing costs again this year. Now, just 15 percent of respondents expect this from the Fed, according to the second quarter survey.

Instead of hiking, the majority of economists (45 percent) now say the Fed will be on hold for the next year.

“Despite a strong domestic economy and job market, the global economy is slowing, financial markets are skittish, and inflation is low, all leading the Fed to take this ‘wait-and-see’ approach,” says Mike Fratantoni, chief economist at the Mortgage Bankers Association.

That’s in line with what officials have communicated. Records of the Fed’s April-May policy meeting show that officials expressed interest rates would be on hold for “some time,” even if the economy shows improvement. In its March projections, the Fed slashed its forecasts for growth and signaled through it’s so-called dot plot that it also would not be raising interest rates for the rest of this year.

But as trade tensions ramp up even further, with the Trump administration threatening additional 25 percent tariffs on virtually all of China’s remaining imports, the picture has looked even gloomier. Forty percent of economists now say that the Fed will be forced to cut rates this year — an outcome that not one economist had expected during the first quarter survey.

“By the first quarter of next year, the economic slowdown will be visible enough to prompt a rate cut from the Fed,” says Scott Anderson, chief economist at San Francisco-based Bank of the West.

Market participants see it that way as well, with nearly 98 percent of investors betting the Fed will cut rates in January. That total was 53 percent a month ago, according to CME Group’s FedWatch.

Though many Fed officials have made clear that it’s too soon to cut rates, such as Chicago Fed President Charles Evans, others have explicitly stated that it might be in the cards. St. Louis Fed President James Bullard said Monday that an interest rate cut could be “warranted soon,” in light of these escalating uncertainties and low inflation, which has stubbornly remained below the Fed’s 2 percent objective.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said Tuesday that the committee would be closely monitoring the situation and is prepared to “act as appropriate to sustain the expansion,” thought that doesn’t explicitly mean that the Fed is going to cut rates.

Where will the job market head in the year ahead?

But amid these uncertainties, one aspect of the current expansion has continued to flex its muscles: The U.S. job market.

Over the past three months, the U.S. economy has created an average of 169,000 new jobs each month. The exceptionally low number of new positions added in February was higher than initially reported, while the unemployment rate in April dropped to 3.6 percent, which is now the lowest level since December 1969.

To date, the current expansion has added more than 20 million new positions during more than 100 months of job gains.

Strength in the job market should continue, economists said in this latest survey, with the average forecast calling for monthly payroll gains of 153,380. Though that’s down from the three-month moving average and what the prior survey called for (165,905), it’s still enough to stay ahead of population growth, says Greg McBride, CFA, Bankrate’s chief financial analyst.

Forecasts have likely shifted lower because of tightness in the labor market, he says. Employers across the U.S. have said it’s difficult to find enough workers to fill open positions, holding down the pace of growth, according to the Fed’s April Beige Book. Employers in the Chicago Fed’s district, for example, were in such need of lower-skilled workers that they reported an “increased willingness to hire and keep workers who had failed drug tests.”

“The primary challenge of the labor market is supplying need skilled labor in sectors like construction, transportation, and manufacturing,” says Robert Dietz, chief economist at the National Association of Home Builders. “A renewed focus on community college and trade schools will lift worker productivity and fill the large number of open, unfilled positions in the economy.”

Where can you expect the 10-year Treasury yield to go?

The 10-year Treasury yield has been trading below the rate of the three-month bill since May 23 — a metric that many experts call a “recession predictor,” as it means that investors believe it’s riskier to trade over the short term than the long term. But that likely won’t last for long, if economists’ predictions come true.

The average of all economists’ forecasts calls for a 10-year Treasury rate of 2.67 percent. Though that’s down from the 3.04 percent forecasted in the prior quarter, it’s higher than where the rate is trading now: 2.10 percent, as of Wednesday.

The main cluster of agreement lies between 2.59 percent and 2.94 percent. If the 10-year yield were to reach the upper bound of that projection, it would be at a level that hasn’t been reached since the beginning of December 2018.

Twenty percent of economists surveyed expect that the yield will be higher than 3 percent, while 30 percent are predicting a yield of 2.5 percent or less.

Where will growth be heading?

Last year was a banner year for both the domestic and the global economy. Countries were expanding across the world, and gross domestic product (GDP) in the U.S. — the total output of goods and services — reached nearly 3 percent, the strongest since 2015.

This year is shaping up to be much different, with growth looking like it’s peaked.

The survey also asked economists whether that assessment was true. The overwhelming answer? Yes.

“The U.S. annualized GDP growth rate has peaked this cycle. It is unlikely that there will be another quarter with a 3 percent or higher growth rate anytime soon,” says Bernard Markstein, president and chief economist at Markstein Advisors. “Investment appears to slowing. Consumer spending is likely to slow in the face of higher prices due to increases from imported goods.”

Economists partially blame slower growth on fading fiscal stimulus. The Trump administration’s tax cuts in 2017 helped provide a boost to growth, sending the U.S. economy on a sugar high and propelling growth in the second quarter of 2018 above a whopping 4 percent. That lift, however, appears to have all but faded, economists said.

But the other culprit is the escalating trade war with China. The Trump administration on May 10 hiked tariffs to 25 percent on $200 billion worth of goods and now threatens to tax all remaining Chinese imports. This is expected to weigh on consumer spending, as well as business confidence and investment, economists in the survey said.

“The trade shock will yield a recession, or near to one,” says William Poole, distinguished senior scholar at the Mises Institute who formerly served as president of the St. Louis Fed. “Thus, growth in 2019 will slow.”

Consumer takeaways

Though the U.S. economy has been sending off some mixed messages, it’s continuing to hum along, with low unemployment and rising incomes, McBride says.

Meanwhile, expectations for the 10-year Treasury yield indicate that the mortgage benchmark could start to pick back up from its current near two-year low. Those shopping around for a home loan should compare mortgage lenders to make sure they’re getting the best rate possible.

But perhaps the most pressing issue is the growing uncertainties that are clouding the outlook and threatening the expansion altogether. It’s important to start preparing for the next downturn now, McBride says.

“Eighty percent of the economists polled see the risks as tilted toward the downside,” he says. “Heed the warning and stabilize your finances now. Boost your savings, pay down and pay off high-cost debt to create some breathing room in your budget that may come in handy whenever the economy slows and your income is reduced.”

Methodology

The Second-Quarter 2019 Bankrate Economic Indicator Survey of economists was conducted May 21-29. Survey requests were emailed to economists nationwide, and responses were submitted voluntarily online. Responding were: Scott Anderson, executive vice president and chief economist, Bank of the West; Scott J. Brown, chief economist, Raymond James Financial; Robert A. Brusca, chief economist. Fact and Opinion Economics; Diane Swonk, chief economist, Grant Thornton; Ryan Sweet, director of real-time economics, Moody’s Analytics; Daniil Manaenkov, chief U.S. economist, RSQE, University of Michigan; Sarah House, senior economist at Wells Fargo; Jack Kleinhenz, Ph.D., chief economist and principal, Kleinhenz & Associates; Bernard Markstein, president and chief economist, Markstein Advisors; Robert Dietz, chief economist, National Association of Home Builders; Joel L. Naroff, president, Naroff Economic Advisors; John E Silvia, president, Dynamic Economic Strategy; Gregory Daco, chief U.S. economist, Oxford Economics; William Poole, distinguished senior scholar, Mises Institute; Lynn Reaser; Bob Baur, chief global economist, Principal Global Investors; Mike Fratantoni, chief economist, Mortgage Bankers Association; Dan North, chief economist, Euler Hermes North America; Bob Hughes, senior research fellow, American Institute for Economic Research.

Learn more:

- Watch for these 6 indicators to know when a recession could be on the horizon

- 5 ways to help make your career recession-proof

- Nearly half of Americans say Washington politics is the biggest threat to the economy

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.