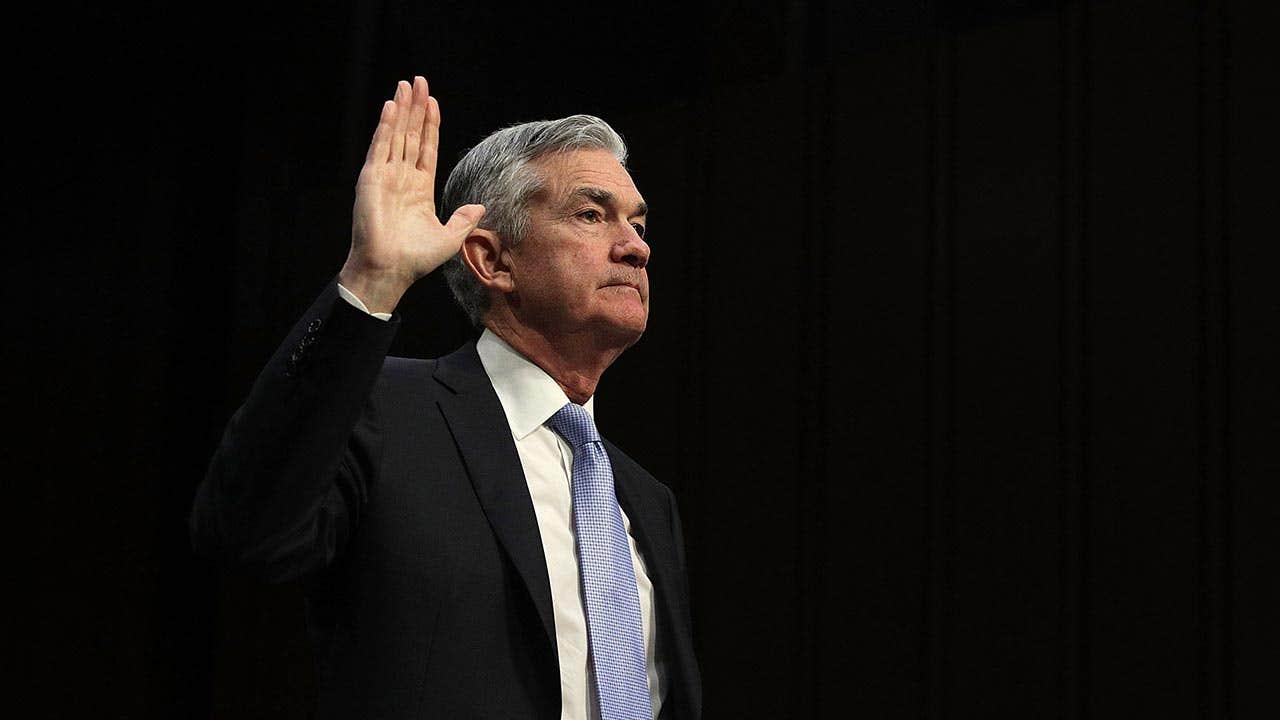

Meet Jerome Powell, the new chair of the Federal Reserve

Jerome Powell was confirmed by the Senate in January to become the 16th chair of the Federal Reserve, and occupied his new post on Feb. 3, replacing the successful and widely admired Janet Yellen. The March FOMC meeting will be his first as Fed chair.

The former private-equity banker and Fed governor has big shoes to fill. Yellen and her predecessor, Ben Bernanke, navigated the nation’s central bank through turbulent waters, implementing unprecedented policies that helped the nation’s economy recover from the worst recession in generations.

Powell faces different challenges, including unwinding the Fed’s tremendous balance sheet without disturbing markets and increasing short-term interest rates without stymying recently improved economic growth. He’ll also have to contend with stubbornly low inflation, and weak wage growth, which bedeviled both Bernanke and Yellen.

The path he sets will impact the paychecks, and savings accounts, of millions of Americans and investors around the world.

Who is Jerome Powell?

Powell is well steeped in the worlds of high-finance and economic policy.

A lawyer who enjoyed stints in well-known investment banking and wealth management firms, including Dillion, Read & Co., Bankers Trust and Carlyle Group, Powell also served in George H.W. Bush’s Treasury Department as under secretary of finance and was a visiting scholar at the Bipartisan Policy Center, where his work illuminated the dire consequences of failing to raise the debt ceiling.

President Obama tapped Powell in late 2011 to fill an open seat on the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors, and he was again nominated and confirmed in 2014.

What kind of Fed chair will he be?

Powell is widely viewed as a centrist who will continue Yellen and Bernanke’s bias towards data-dependent decisions to raise short-term interest rates.

Analysts expect three hikes this year, after three hikes last year, as the economy continues its steady convalescence from the Great Recession. The number of rate hikes could increase should the recent tax cut bill cause growth to accelerate.

“The rate path may be steeper but not because of a different approach to monetary policy, but rather because of a pickup in growth spurred by fiscal policy and higher inflation,” says Point Loma Nazarene University chief economist Lynn Reaser.

In fact, Powell’s down-the-middle approach is evident when you look at the political breakdown of his confirmation vote.

In 2012, when President Obama resided in the Oval Office, almost half of Senate Republicans voted against Powell’s nomination, along with only one member of the Democratic caucus—Sen. Bernie Sanders (I–VT). Six years later, after the Fed had helped nurse the nation back to health, all but four Republicans voted for Powell, while nearly one-fifth of Senate Democrats voted nay.

One of those four, Senator Mike Lee of Utah voted against Powell’s confirmation all three times because the new chair doesn’t support legislation that would open the Fed’s policy discussions to review by the Government Accountability Office, according to a spokesperson.

Still, Powell is someone a decent chunk of both parties can oppose only when the other party nominates him.

What does this mean for me?

The Fed has two core responsibilities: maximize employment and keep inflation stable, with a goal of 2 percent annual growth.

Over recent years, the latter has proved much more difficult to execute than the former. Prices have risen well below the Fed’s goal, despite the unemployment rate hitting levels not seen since the beginning of the century.

When testifying before the Senate Banking Committee, Powell affirmed that weak price increases have bedeviled Fed officials, and that the pace of interest rate hikes could slow if stronger inflation doesn’t materialize.

But don’t expect Powell—who’s a Republican, after all—to implement a more dovish policy than Yellen. While nearly three-quarters of economists surveyed by Bankrate believed that Powell will follow his predecessor’s roadmap, none believed he would enact more dovish policy.

“I expect Chair Powell to continue on Yellen’s trajectory, with a gradual normalization of rates so long as inflation does not retreat,” says University of Maryland professor Phillip Swagel.

Powell will also assume control of the Fed’s effort to unwind its balance sheet that hit around $4.5 trillion in assets without upsetting markets, or driving up bond yields dramatically. The Fed will eventually cast off $50 billion worth of debt every month, and it’s an open question of what that will do to, say, the 10-year Treasury yield, which affects the rate you’ll pay for your mortgage.

Will hawkish monetary policy eventual lead the economy back into recession? The current business cycle can only go on for so long.

In the short term, expect your credit card APR to increase over the next year, while yields on savings accounts and CDs slowly perk up.

Savers, for the first time in a decade, have the wind at their backs.

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.

You may also like

How the Federal Reserve impacts savings account interest rates