Here’s what the Fed has to see before lifting interest rates from rock bottom

The Federal Reserve is hunkering down for a long battle against the coronavirus crisis – a defensive position that will likely mean keeping rates at zero for years to come over fears that the pandemic has left a lasting mark on the U.S. economy.

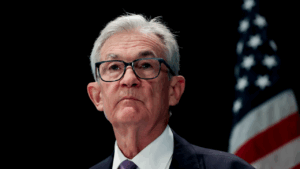

The longest expansion on record was ripped right out from underneath Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, who, until about two months ago, was presiding over the U.S. central bank at a time when unemployment had taken a welcomed descent to its lowest levels since the 1960s.

Now, Powell’s having to mobilize the Fed to move farther and faster than ever before as the novel coronavirus pandemic throws a wrench in the gears of the financial system. Efforts to contain the spread have left nearly one in five U.S. workers out of a job and forced restaurants, bars, retailers, gyms and theme parks – the engines of economic growth – to close.

Powell struck a candidly solemn tone as he wrapped up the Fed’s two day meeting Wednesday at a historic virtual press conference, outlining behind the digital lectern one of the Fed’s greatest fears: That the pain will persist long after the shutdowns end, leading to a slow and grueling economic recovery.

All of this suggests that it will take a long time before the economy rebounds at the “solid” pace officials say they want to see before lifting rates again.

Fed’s whatever-it-takes moment will be tested by slow rebound

Powell & Co. have gone all-in to blunt the economy’s free fall, slashing the federal funds rate to zero, instituting a massive bond-buying program to prevent markets from collapsing and creating 11 new emergency lending facilities to guide credit toward some of the hardest-hit households and businesses.

Powell appears committed to maintaining zero rates all without giving many specifics. He stressed that officials are “not going to be in any hurry” to retreat from those emergency steps, adding that the Fed would like to see that the economy has “solidly” weathered and rebounded from the economic crisis.

But the Fed suggested it doesn’t see that happening anytime soon. Officials in their post-meeting statement said the coronavirus crisis poses a threat to the outlook “over the medium term.” Powell outlined expectations for unemployment to remain elevated for a while and an overall unlikelihood that the economy returns to previous levels before the crisis right away.

It’s a contrast from the “V”-shaped recovery that investors and the Trump administration are betting on.

“We’re still putting out the fire. We’re still trying to win,” Powell said. “And I think we’ll be at that for a while.”

“At this point, the Fed has committed to perpetually being on the sidelines for as long as needed,” says Lindsey Piegza, chief economist at Stifel. “The optimism for a flip-the-switch scenario – that’s far outweighed by the risks that we will see a structural displacement of economic activity.”

Expect a green light for rate hikes after wages, participation come back

How soon the economy can recover depends on how much steam it has left once the recession ends. A large source of economic fuel is the job market, and how long individuals are out of work has grave consequences. The longer unemployment lasts, the more likely workers will lose skills or touch with the labor force.

Falling participation rates became the most popular labor market narrative from the Great Recession of 2007-2009. Severe job loss and a tough job-seeking environment discouraged workers so much that they dropped out entirely from the workforce.

Once those participation rates fell, they became sticky. By the time the decade-plus expansion ended, the U.S. economy had finally managed to rope back most of the prime-age workers that it lost to the previous downturn, though it never fully recovered.

Individuals have already dropped out of the labor force since the pandemic suffocated the labor market. Participation rates in April plunged to the lowest level since May 1983.

Managing it is a tough task for policymakers. It requires not only getting the economy back up to speed, but running it hot enough at those levels for a long enough time that it entices people to come back. The Fed will likely keep an eye on wage growth numbers and participation rates to see whether the labor market has more workers on the sidelines before lifting rates again.

“There’s just a lot of people who will say, ‘I’m not going back to work; I’m done,’” says Joe Kalish, chief global market strategist at Ned Davis Research. “It doesn’t take a lot more to say, ‘Hey, do I really want to battle my way back into this thing?’ You may never get those people back.”

Fed will watch unemployment rates, but don’t expect a quick rebound

The other issue is that many shuttered businesses won’t survive the crash, which makes finding a job an even tougher task for those willing to hunt in a poor economy. Nearly 7.5 million small businesses are at risk of closing permanently because of the coronavirus pandemic, according to an April survey from Main Street America.

“That could be damaging to the performance of the economy over time,” Powell said. “These thousands of great medium- and small-sized businesses that we have all over the country – they’re worth so much more to the economy than the sum of their net assets.”

National firms aren’t free from pain, either. National retailers J.Crew and Nieman Marcus filed for bankruptcy this week, two of the earliest casualties during the coronavirus pandemic.

It could lead to a harrowing economic reality when it comes to the coronavirus: Unemployment won’t likely plunge as quickly as it surged. It took nearly eight years for joblessness to rebound to its pre-recession lows following the 2007-2009 downturn, after peaking at 10 percent in Oct. 2009.

Some of the tens of millions who have applied for unemployment insurance could still have ties to their jobs. But even if a few of their former employers are lost to the pandemic, it’s unrealistic to expect the U.S. economy to be able to immediately create enough jobs to plug the gap.

It took more than a decade for the U.S. economy to create about 21.5 million jobs during the previous expansion, a pace of about 2 million a year. Even if two-thirds of the individuals on unemployment benefits are able to return to where they worked before the pandemic, that would still leave behind about 10 million people.

“The unemployment rate should come down a lot faster than last time as the economy starts to reopen,” says Jay Bryson, managing director and acting chief economist at Wells Fargo. “But for our businesses who have gone out of business, they’re not coming back. And for the people who got displaced, they don’t have a ready job to come back to like some of those people who have been furloughed.”

Given that one of the Fed’s two mandates is maximum employment, odds are officials will want to see the job market make significant progress before tapping the brakes on its emergency measures.

Fed may be comfortable letting inflation run above target

Former Fed Chair Janet Yellen steered the U.S. central bank away from rock bottom rates in 2015, when unemployment reached about 5 percent. But today’s Fed might be comfortable letting unemployment fall even lower than that. A good ballpark could be the Fed’s forecasts for the natural rate of unemployment before the coronavirus crisis: 4.1 percent.

“We were hearing from low- and moderate-income and minority communities that this was the best labor market they’d seen in their lifetime. All the data supported that as well,” Powell said. “And it is heartbreaking, frankly, to see that all threatened now.”

It has some consequences for the other side of the Fed’s mandate: stable prices. Experts say Fed officials won’t forget that they had been missing their 2 percent inflation objective for much of the previous expansion. That might mean today’s crop of Fed policymakers will be fine with letting it creep well above that threshold for a period of time.

“Last year before the crisis, the Fed was dialing things back already, saying we just haven’t fulfilled our mandate,” Kalish says. “If you look at the Fed’s primary mandate of stable prices and maximum employment, it’s really hard to walk away with this idea that they’re going to be raising rates anytime soon.”

Even then, it’s unclear how much of an issue inflation will be in the near-term. Shortages could lead to building price pressures, but that might be offset by falling oil prices and an overall weak economic outlook.

“The Fed has been struggling with inflation for the past several decades,” Piegza says. “That coupled with the forecasts for a relatively hard hit for the economy, it’s going to be quite some time before inflation is a concern.”

Fear while returning to normal could prolong consumer spending, business investment slump

States have started wading into the waters when it comes to reopening the economy, but that process might not be the “Field of Dreams” if-you-build-it, they-will-come scenario the Trump administration is envisioning. Powell underscored that consumers might need some time before returning to their normal way of life, out of fear that they’d catch the virus. A second wave could also pose another threat to the snapback, if it proves to be bad enough to warrant another round of shutdowns.

“A lot of it depends on how comfortable people feel on going back to what they were doing before,” Byron says. “If people aren’t spending as much, it could cause the overall economy, the growth rate, to be somewhat sluggish and the unemployment rate to remain high.”

It means the economy’s recovery is just as contingent upon a vaccine or medical treatment for the pathogen as it is on stores and restaurants being able to open again to full capacity. And it paves the way for a continued slump in consumer spending.

Choppy waters may also be ahead for business fixed investment. Businesses might be just as hesitant as consumers to make long-haul decisions, which has broader implications for productivity and unemployment.

“This just came out of left field. Do you want to invest as much, everything else equal, if suddenly your world has been rocked?” Bryson says. “If we’re not investing as much as we were before, it has some knock-on effects on productivity for some time.”

The U.S. economy contracted by the most since 2008 in the first three months of 2020, according to gross domestic product figures released by the Department of Commerce. An even more catastrophic plunge is expected for the second quarter. Fed officials will likely pay attention to the gap between the economy’s potential and its current performance, which experts refer to as the output gap.

Fed can’t fix all of economy’s problems

Illustrating that it’s going to be a long road ahead for Fed officials, Powell underscored that Fed policy can’t fix all of the U.S. economy’s problems. He used it as an opportunity to highlight how important fiscal policy will be – a practice monetary policymakers typically steer clear of to bolster Fed independence.

“Lowering interest rates cannot stop the sharp drop in economic activity caused by closures and other forms of social distancing,” Powell said. “It may well be the case that the economy will need more support, from all of us, if the recovery is to be a robust one.”

Powell continued to stress that the Fed has lending powers, not spending ones. It means the Fed can only make loans, not grants.

But even if the U.S. central bank’s powers are somewhat limited, Powell emphasized the Fed is still willing to do whatever it takes until the economy is back on its feet. It’s just a path wrought with unknowns – meaning the Fed will be in data-dependency mode.

“There’s so much uncertainty about the economy, and more, there’s so much uncertainty about how this pandemic is going to evolve from here,” Bryson says. “We’ve never seen anything like this in our lifetimes before. How does an economy evolve when it’s been completely shut down? None of us really know.”

Learn more:

- When will the U.S. economy get back on track following coronavirus shock? Watch for these 5 signs

- Coronavirus pushes home sales off a cliff. When will they recover?

- Stimulus checks: What consumers should consider doing with the money

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.

You may also like

Fed holds interest rates steady, resisting pressure from Trump