The budget deficit, explained — and how to prepare for a rising tax burden down the road

Avoid spending more than you make: That’s a tried-and-true piece of financial advice and is perhaps the simplest, most basic lesson when it comes to managing your wallet.

That same advice, however, doesn’t always apply to the federal government, with President Donald Trump and Republican leaders’ plans to cut taxes often at odds with spending proposals championed by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and other Democrats, resulting in an unbalanced budget with a deficit.

The “budget deficit” is a closely watched aspect of Congressional policy and government spending, and while many experts caution that it isn’t so much worth worrying about right now, it might come with a higher tax burden down the road.

Here’s everything you need to know, including what the budget deficit is, why it matters, how it works and how it could impact you.

What is the budget deficit?

The budget deficit isn’t as complicated as it sounds: It occurs when the federal government spends more than it takes in. It isn’t, however, to be confused with federal debt, which is the total net sum that the government owes. Debt happens when deficits snowball.

To distinguish between the two, think about your own personal finances. Say you’re spending about $100 more a month than you’re making; that’s your budget deficit, which will accrue to $1,200 after a year. Ten years from now, if you continue on this path, you’d be in debt by $12,000.

“One can think of a deficit as the annual imbalance between what the government spends and what it takes in, and the debt, which is a long-term gap between the government’s commitment to spend and the ability it has to pay for those intentions,” says Mark Hamrick, Bankrate’s senior economic analyst and Washington bureau chief.

The government mainly earns money through tax revenues, with personal income taxes the largest generator, followed by payroll taxes and corporate taxes, among other smaller measures. It then spends money to fund programs such as Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid and Veterans benefits, as well as other discretionary items, including national defense.

But Congress’ massive coronavirus response — which included passing a $2 trillion-plus stimulus package, the largest in American history — illustrates that the federal government doesn’t always earn enough to offset the costs of what it has to pay for, though this isn’t just an occurrence isolated to times of deep and severe recessions.

How wide is the budget deficit?

The federal government last closed the budget deficit in the late-1990s during the Clinton administration, and the U.S. even went on to have a surplus of $236 billion in 2000. That continued for two more years, until the dot-com bubble burst. The Great Recession of 2007-2009 then only put it in a worse-off position.

Yet, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 renewed experts’ worries about the deficit, followed by the government’s coronavirus response.

“The deficit recently has been a function of a large amount of spending in response to the pandemic as well as a reduction in tax revenue, beginning with the 2017 Trump tax cut,” Hamrick says.

Forecasts are already suggesting that the budget deficit will reach its widest on record because of the pandemic-induced recession response. Treasury Department data shows the U.S. having a $3.007 trillion year-to-date deficit, nearly triple the $1.067 trillion that was seen at this time last year. That total also eclipses the $1.4 trillion annual deficit in 2009, which at the time was the largest on record. Total debt is also well past $26.781 trillion, as of September 2020, according to the Treasury.

How does the budget deficit work?

You might be wondering how exactly the government can spend more than it earns.

To finance what can’t be paid for with revenue, the federal government issues U.S. Treasurys. Investors — which can include businesses, individuals and even other countries — purchase those bonds because they’re generally considered to be a safe investment, given that the federal government has never defaulted.

The Federal Reserve also plays an indirect role. To help prop up the economy and stimulate growth, the U.S. central bank has been buying U.S. Treasury debt in the secondary market, rather than from the Treasury Department itself. At the end of 2019, the Fed owned about $2.321 trillion worth of Treasurys, which was about 13 percent of the total debt outstanding, according to the Congressional Budget Office. As part of its coronavirus response, however, the Fed now owns even more: as of September 17, $4.402 trillion, or about 16 percent of total outstanding debt.

In theory, there isn’t a limit to how wide a budget deficit can get. “It can go as wide as the government wants it to and the American people let it,” Hamrick says.

Why would a government run a budget deficit?

Budget deficits often increase during recessions as governments finance special aid programs in times of economic distress. That’s so it can do things like send $1,200 (or more) stimulus checks to Americans to get through a crisis. But even in boom times, the budget deficit has been just a part of American life.

Generally speaking, to trim a budget deficit, you would either have to cut back on spending or raise taxes. Politicians in Washington haven’t been in any hurry to do those things, though they’re hesitant to rack it up even more. Republican lawmakers in Congress are expressing concerns about spending their way out of the coronavirus-induced downturn, and largely, worries about throwing out too much money have been the underlying reason for gridlock on Capitol Hill in the race to enact more aid.

“There are few members of Congress in either party these days who make it a priority to ensure that there is sufficient tax revenue generated to pay for what lawmakers and the president have already agreed to spend,” Hamrick says. “That’s where the problem begins.”

How worried should you be about the budget deficit?

Generally speaking, experts worry when debts and deficits grow faster than the economy. And the bigger they grow, the harder they are to wrangle down, which historically can lead to a debt crisis, as was the case for Greece.

Another part of the concern is that the deficit — what’s right now 17 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), a record — could spark inflation, as the federal government ramps up spending and increases the money supply. However, today’s period of historically low interest rates, sluggish growth and tepid price pressures have made those risks seem minimal.

But it might not be so much the deficit itself that causes problems; rather, the act of closing it. Given that closing the deficit involves cutting back on spending or raising taxes, that could restrict economic growth and put more burden on taxpayers down the road.

Another key problem is that, the wider the deficit grows, the more money the federal government spends on paying interest. With interest rates at historic lows, that hasn’t been so much of a burden, but it still ties down cash.

“It is already a concern to the extent that lawmakers are cautious, or unwilling, to spend on other things,” Hamrick says. “Many Americans would like to see health care reform. But cost is a huge concern particularly when debt and deficits have risen sharply in recent years.”

And eventually, when the Fed starts raising interest rates again and tapering back on its bond-buying programs, that might put the federal government between a rock and a hard place with rising interest rates.

However, that appears unlikely to happen at least anytime soon, with the Fed expecting to keep rates low for at least three more years.

How to safeguard your finances

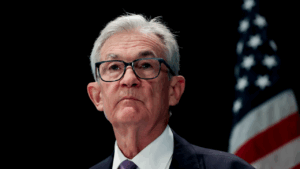

But while it might seem that the federal government has a few monsters in the closet, take solace in words from Fed Chair Jerome Powell, who has been long regarded as a deficit hawk.

Powell in a May video conference with the Peterson Institute for International Economics stressed that deficits and debts are not worth worrying about right now. In fact, Powell has repeatedly been vocal about the concerns of not spending enough to help Americans and businesses get through recessions similar to the coronavirus pandemic.

If business failures become widespread and Americans face a substantial income loss, that might weigh on the economy over time, leaving it in a worse-off position.

“Additional fiscal support could be costly but worth it if it helps avoid long-term economic damage and leaves us with a stronger recovery,” Powell said.

Americans, however, can still take steps to safeguard their finances from ballooning federal deficits. As is always prudent financial advice, saving for retirement and emergencies is a priority and repeatedly listed as one of Americans’ top regrets. A deficit only underscores those priorities and might light a fire under investors’ and savers’ plans to find more tax-advantaged investment options, Hamrick says.

“If there’s a higher burden down the road related to rising interest rates and taxes, that would tend to create added stress on personal budgets,” Hamrick says. “No matter what, I’d rather see people try to save aggressively than to fail to make it a priority. Better to be ahead of the game than behind it.”

Learn more:

- What is economic stimulus and how does it work?

- Negative interest rates, explained — and how they work

- What is the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet?

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.

You may also like

Passive income: How is it taxed?