Will the government default? Everything you need to know about the debt ceiling — and how it could impact you

Lawmakers on Capitol Hill have less than a month to avert an unprecedented economic disaster and increase how much money the federal government can borrow — or get rid of those caps altogether.

If they don’t, analysts say Americans could experience anything from a financial crisis and a recession to job losses, higher inflation and even more expensive borrowing costs.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said in a Monday letter to Congress that the U.S. could be unable to pay its bills by as early as June 1, meaning the federal government is at risk of defaulting for the first time in history. The news comes nearly three months after the federal debt reached its $31.4 trillion mandated limit on Jan. 19.

Since then, the Treasury Department has been playing the most important game of musical chairs in finance, reshuffling money around through “extraordinary measures” to keep covering the government’s obligations despite being barred from borrowing any more money to fund the government.

Those efforts include suspending contributions and reinvestments into retirement funds for federal and postal service employees. Once the impasse is resolved, Yellen said the agency would make those funds whole again.

Yet, the key official’s latest letter indicates lawmakers have even less time to reach an agreement than they originally thought. The agency had originally estimated it could buy legislators time through early June but revised those deadlines amid smaller-than-expected federal tax receipts.

To address the issue, Congress will have to either vote to raise the limit or suspend it altogether. Lawmakers haven’t been shy about taking either of those steps before. Since 1960, Congress has adjusted or suspended the statutory debt limit 78 times, according to the Treasury Department.

What is the debt ceiling?

For centuries, the U.S. has spent more money than it takes in — meaning it runs a budget deficit. Most recently, the deficit hit $1.1 trillion in the first half of the government’s fiscal year (October through April), according to the Treasury’s monthly budget statement.

That financing is how the government pays its bondholders, funds its operations and covers mandated mandatory-spending programs, from Social Security and Medicare, to military salaries, tax refunds, national interest payments and more.

The Treasury Department finances that extra spending by selling government securities. Yet, lawmakers don’t just hand the agency a blank check. Instead, Congress, since 1917, has limited how much the Treasury Department can borrow. That guideline is known as the “debt ceiling.” Think of it like the credit limit on a credit card.

But unlike what happens when you use up your credit line, Congress isn’t cut off from spending once it reaches that limit. Lawmakers can — and do — keep committing to new spending, after which the debt ceiling isn’t automatically raised.

It is an ineffective tool, which has failed to keep the federal debt from expanding. There are a number of more optimal paths forward, including having lawmakers avoid passing budgets that aren’t balanced, or even doing away with the debt ceiling itself.— Mark Hamrick, Bankrate Senior Economic Analyst

Addressing the debt ceiling doesn’t come with a cost to taxpayers or bring new spending commitments. Rather, it allows the government to continue financing the spending and obligations previous Congresses and presidents already committed to.

Both parties have contributed to those massive deficits. Republicans and Democrats approved $3 trillion in deficit-financed spending under President Trump in 2020, according to estimates from Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics. The Democrat-approved American Rescue Plan cost nearly $2 trillion in deficit-financed spending, while the Republican-supported Tax Cuts and Jobs Act required another $2 trillion.

What is happening on Capitol Hill?

Political gridlock can make the situation more dire, with legislators often leveraging the deadline to spur concessions.

Spearheaded by Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.), the House of Representatives passed a bill on April 26 that would raise the debt ceiling by another $1.5 trillion or suspend that limit through March 31, 2024 — whichever comes first. The legislation would also curtail some of the Biden administration’s key spending programs, such as the Inflation Reduction Act’s energy and climate tax credit expansions and federal student loan forgiveness. Savings would total $4.8 trillion over the next decade, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

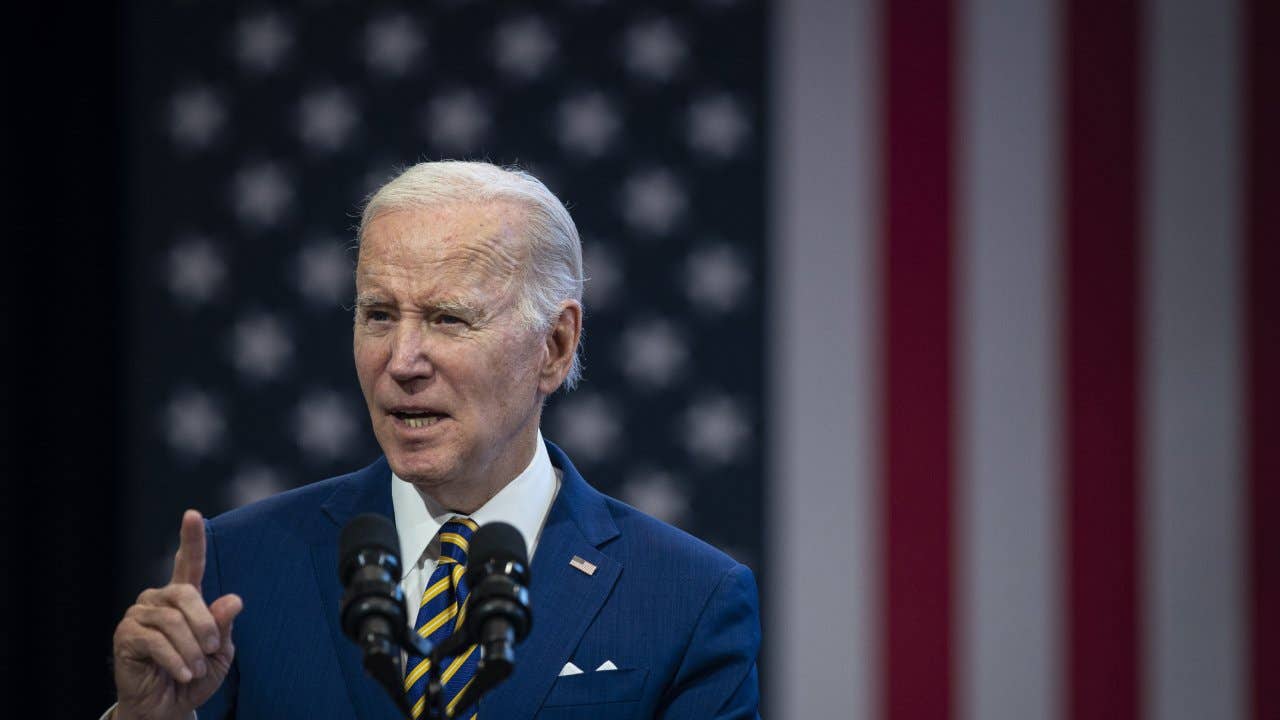

President Joe Biden has threatened to veto and opposed the legislation in an April 25 statement, citing a Moody’s analysis that it could lead to 780,000 fewer jobs by the end of 2024 — and “meaningfully increase” the likelihood of a recession, the report shows.

Biden is planning to meet with McCarthy, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-New York) and Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky) for talks on Tuesday.

“The House passed a reasonable bill that would raise the debt limit, reduce deficits, and slow the growth of our national debt,” says Maya MacGuineas, president of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. “We need to raise the debt limit as soon as possible, without drama and without serious risk of default.”

Biden is also looking into whether he can constitutionally challenge the debt ceiling by invoking the 14th amendment, which states that the “validity of the public of the United States … shall not be questioned,” according to reporting from The New York Times.

Another more extreme action could involve the Treasury Department minting a $1 million platinum coin, a step experts say is less likely.

What could it mean for the economy?

Each day lawmakers don’t act could raise the risks. Yellen has said the U.S. defaulting on its debts could cause “irreparable harm” to the U.S. economy, with borrowing rates on things like credit cards, mortgage rates and auto loans skyrocketing.

Those consequences would add to the challenges the U.S. economy has already been facing before any debt limit showdown showed up: a slowing economy, rising interest rates and high inflation. The Federal Reserve at its May meeting lifted borrowing costs to the highest level in nearly 16 years.

The U.S. has never defaulted on its debts, making the prospect uncharted territory and especially difficult to forecast the impending economic effects. RSM Chief Economist Joe Brusuelas says joblessness could surge anywhere between 7 percent to higher than 12 percent, depending on how many bills the government can’t pay and how long the government remains in default. Brusuelas also estimates inflation could surge around 10-11 percent as the economy claws its way back.

Fed officials have so far been mum on commenting about fiscal policy matters, though a default crisis could prompt their involvement to keep financial markets from seizing up. If the worst-case scenario of default occurred, Fed officials may be willing to do anything from lending money to banks through its discount window to injecting cash in the short-term market for repurchase agreements to prevent interest rates from soaring, transcripts from a 2013 debate reveal.

Powell said purchasing securities with delayed payments or even swapping them with non-defaulted Treasurys would be “loathsome,” but that he’d be willing to accept it under “certain circumstances,” the transcripts indicate.

“The Fed will move in advance of any debt ceiling debacle to reassure financial market participants of the quality of U.S. issued paper,” Brusuelas says. And “if necessary, will move to purchase such paper to ensure the functioning of financial markets.”

Moody’s Analytics has previously estimated default could result in a 2008-style financial crisis, weighing on Americans’ livelihoods and retirement balances. During previous simulations from 2021, the firm said economic growth could shrink 4 percent from peak to trough, while 6 million jobs could be at stake. Joblessness could also hit 9 percent, and household wealth could fall by $15 trillion during a massive stock market decline.

The extent of the impact also depends on how the government prioritizes which bills it pays — and which ones it doesn’t. Lawmakers have indicated they may want the Treasury Department to prioritize paying bondholders before military salaries and retirees.

The Treasury Department could also choose to make no payments at all until it has enough cash to cover all of its obligations, according to the agency’s contingency plan for a similar debt ceiling impasse in 2011.

The Treasury Department makes more than 80 million payments per month, all of which are at risk of not being paid on time, the report also said. The federal government would even be at risk of paying its electric bill late.

“Americans should avoid the temptation to think this is a Washington-only problem,” Hamrick said.

Will the U.S. government default?

Congress has certainly cut it close on raising the debt ceiling before. Yet, experts say the political gridlock has been magnified this time around.

“It is impossible to quantify, but the risk of default is higher than zero,” Hamrick says. “The political process is more fractured than in the previous instances, including 2011. … This is entirely self-inflicted and avoidable.”

Economists fear lawmakers might not speed up talks and reach an agreement until they see signs of trouble — such as massive gyrations in the stock and bond market.

Investors are already behaving as if there’s a risk they might not be paid back. Yields on the one-month Treasury bill, which could mature ahead of the debt ceiling deadline, have surged more than a full percentage point since Yellen’s Monday letter.

“Everybody is busy playing politics, but as we get closer to the X-date, one hopes that they will put the good of the country ahead of political games,” MacGuineas says. “The vast majority of lawmakers know how important this is. They do have an ongoing tendency to only do anything when we bump up against emergency situations.”

5 ways your wallet could be impacted if the government defaults on its debt

1. Government obligations such as Social Security or Medicare disbursements could be at risk

If the debt ceiling binds, the Treasury Department might decide to delay — or temporarily halt — payments to millions of Americans and government agencies. That could be anything from Social Security checks, Medicare disbursements to health care providers, payments to agencies and state and local governments, as well as military and government contractor salaries. The Treasury Department did review that as one of its options in the event of default, the 2012 inspector general report also indicated.

“The Treasury market is viewed as the most liquid and the safest in the world, and it’s a huge benefit to the U.S,” says Louise Sheiner, policy director for the Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy at the Brookings Institution. “The idea that you would undermine those benefits and undermine the whole financial system of the world, which depends on Treasurys to operate, has much larger complications for the economy, than, what at the beginning, is a few days’ worth of delays in [entitlement] payments.”

2. Buying a home, car or credit card borrowing could get more expensive

The federal government can borrow at a relatively lower interest rate than other governments worldwide because Treasury securities are viewed as a safe and liquid investment. But that’s contingent on the federal government never defaulting on its debts.

“The U.S. treasury and U.S. dollar are considered to be the safest assets because America always pays its debt,” says Yelena Maleyev, economist at KPMG. “Trust would be eroded for the global economy when it comes to U.S. debt, and it could really flip a lot of things upside down.”

Once that view is upended, however, investors might demand a higher premium to protect themselves from risk. Higher yields could cause other interest rates throughout the economy to rise, from the mortgage rates that are directly tied to the 10-year bond, as well as credit card and auto loan rates.

“It’s economic disruption,” says Scott Clemons, chief investment strategist and partner at Brown Brothers Harriman. “If you were in the middle of trying to get a mortgage, it would be more expensive to accomplish that. If you’re a small business trying to get a loan, it would be harder. When I’m not sure what the Treasury market is going to do, it makes it really hard for me to lend money because of all of the uncertainty.”

Those consequences could be long-lasting, especially if the fear of another default remains in the back of investors’ minds. Higher interest rates wouldn’t just make the U.S. a more expensive place to live for Americans but could also make both new and outstanding debts costlier.

3. Stock prices could sink, threatening companies’ bottom lines

If the debt ceiling were to bind, markets would likely whipsaw, potentially enduring immediate and steep losses that might take a while to recover — even if the situation is quickly addressed.

From April to August 2011, at the height of a similar debt limit debacle, the S&P 500 tanked 31 percent. By the end of that year, the index had only recovered half of the ground it had lost.

All of that could threaten corporate profitability, and firms that have increased exposure to government spending might take an additional hit. Those could be firms that have contracts with the federal government, as well as insurance firms that derive a certain portion of their revenue from Medicare payments.

“We saw what the risk of just one bank failing to meet payroll, in the case of Silicon Valley Bank, did to the economy and a sector,” Hamrick says. “As we know, depositors were made whole and payrolls were met. Magnify that many times over, and that gives us an idea of what an actual federal default might look like.”

4. Default could trigger a recession, job losses and income disruptions for millions

Even if lawmakers quickly respond and a default is short-lived, it could have massive consequences. Experts describe default as having a ripple effect. Investors who the federal government doesn’t pay back might then be hard-pressed to fund their own obligations, with the circle getting bigger and bigger. The Treasury market is the epicenter of the economy, helping to keep the gears of commerce churning.

“Even if short-term, a default would provide a remedial course in global economics at a very hefty tuition,” Clemons says. “The U.S. Treasury market is like the circulatory system of the global economy.”

On an individual consumer level, Americans might be unable to afford basic necessities if some form of income comes from the federal government. Demand could take a hit, and with company profitability already in question, hiring could hit a wall as well.

Households already lost $7 trillion in wealth last year, thanks to rising interest rates and volatile asset markets, Fed data shows. Meanwhile, joblessness is already projected to rise to 4.6 percent within the next 12 months, according to Bankrate’s Economic Indicator survey.

“The risk and fear of a federal default adds to uncertainty at a time when businesses and households are already dealing with an abundance of it,” Hamrick says. “It will weigh on financial markets and the economic outlook. As we know, recession worries are already elevated and this only adds to the reasons to be concerned.”

5. The Fed could derail its plans to fight inflation and focus on fighting a financial crisis

It’s often the Fed’s job to keep markets functioning. If credit markets were to seize up, the Fed might temporarily sideline its quest to battle inflation in place of policies that can help revive markets.

“Whatever extraordinary measures the Fed would take on could mean that then they take a step away from their fight against inflation,” Maleyev says. “If the Fed is taking its foot off the brake to focus on something else, inflation could come back up.”

Even if the debt ceiling is raised in time, Americans could feel financial pain

During a similar 2013 debt ceiling standoff, yields on the Treasury securities that were nearing maturity rose between 21-46 basis points, in addition to stock markets experiencing volatility, according to a Fed analysis. The average 30-year fixed rate mortgage in the U.S. climbed nearly 124 basis points in the year, according to data from Freddie Mac.

Even if Congress makes a last-ditch effort to raise the debt ceiling and avoids default, Americans might not go entirely unscathed.

“Default is not the only bad thing that can happen,” Maleyev says. “It is the worst thing.”

During a previous credit limit impasse in 2011 federal government previously hit its credit limit in 2011, Standard & Poor’s nixed the U.S.’s top-grade “AAA” credit rating status, citing political brinkmanship that’s made policymaking “less effective” and “less stable.” Experts say that brinkmanship has only gotten worse since then, meaning another credit downgrade could be possible.

Another credit downgrade for the nation could also impact the ratings of institutions that work with the government, as well as those that are government-backed, such as Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and the Federal Home Loan Banks, according to Zandi.

“Ideally, we would return to the practice of lifting the debt ceiling without relying on extraordinary measures,” MacGuineas says. “Politicians who are rightly worried about the nation’s unsustainable borrowing path should take a hard stance against new borrowing and oppose legislation that would add to the debt … rather than threatening not to pay the bills on borrowing that has already been incurred.”

Bottom line

Yellen has repeatedly said she supports erasing the debt ceiling altogether to remove the risk of default every time the federal government approaches its borrowing ceiling.

Americans will want to focus on what they can and cannot control. They can’t do much about the gridlock between Washington lawmakers, but they can backstop their finances as much as possible. Focus on building up an emergency savings, even if it means cutting back on discretionary spending to free up some cash. Investors will want to take a long-term mindset and not overreact to short-term events in Washington that hope to be resolved.

“Clearly, not raising the debt ceiling is a bad thing for the economy, but there’s a lot of uncertainty — if this actually happened — of how it’s going to unfold,” Sheiner says. “Some scenarios are worse than others. None are good.”

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.