Why the coronavirus crisis could cause a double-dip recession — and how to prepare for one

The coronavirus-induced recession has certainly felt like a roller coaster. Now the question is whether it could end up looking like one.

Virus cases are resurfacing across the South and Midwest, eroding consumer confidence and leading to renewed limits on certain business activities. Federal Reserve officials and private-sector economists say it’s slowing the pace of the rebound — but more pessimistic forecasts suggest it could tip the financial system over again.

It means the long-feared W-shaped recession has entered the conversation: A double-dipping downturn, rife with twists and turns, where the financial system descends and recovers but falls again.

“You could say that the economy is in the process of recovering,” says Chris Varvares, co-head of U.S. economics at IHS Markit. “The main point here is, don’t be lulled into some false sense of nirvana and think, ‘OK, thank God, we dodged that bullet.’ The economy started to recover, but it could fade and turn down again.”

The W-shaped recession: A feared, yet rare phenomenon

The W-shaped recession isn’t tossed around as much compared with the other alphabetic recession shapes, from the relatively quick snapback “V” downturn to the “U” recession meaning lower for longer. Economists partially chalk that up to being a less-common pattern.

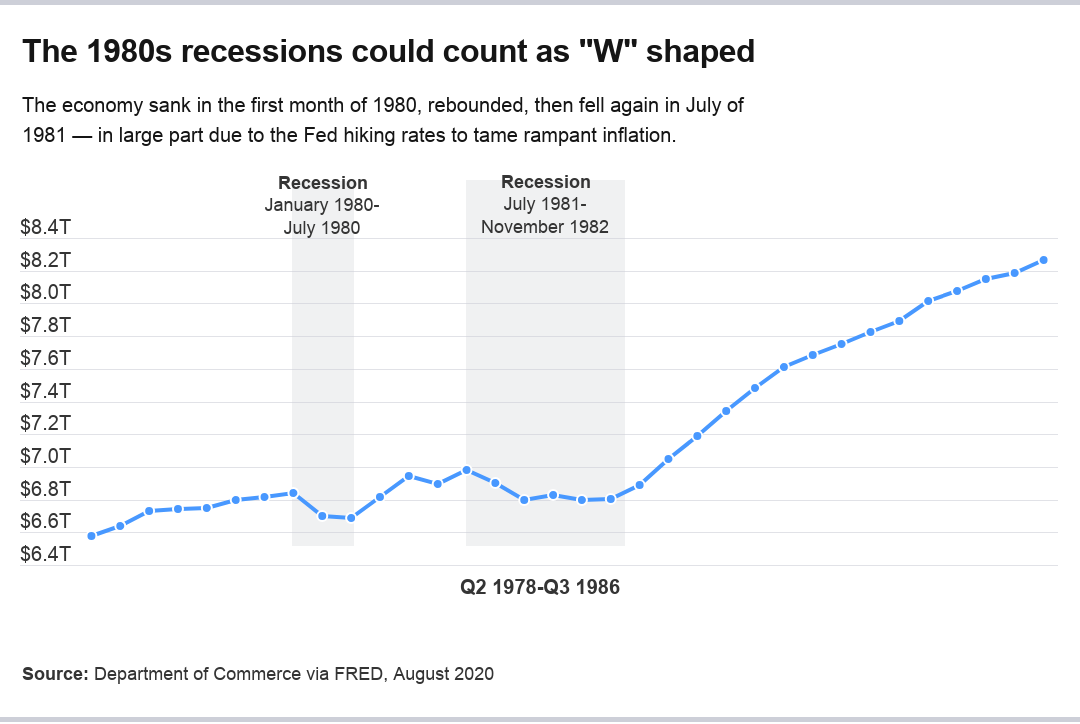

If anything came close, it might be the two recessions in the early 1980s, Varvares says. The downturn was in part man-made, with the U.S. central bank raising interest rates to nearly 20 percent to curb rampant inflation. That aided the economy in the long run, but it was also a policy choice that caused Americans and businesses to dramatically pull back on spending, leaving about 12 million people jobless.

But even then, it’s not a perfect, apples-to-apples comparison. No recession in the post-war period has borne an exact resemblance to the coronavirus crisis.

“It’s a unique situation that’s not part of a normal economic cycle,” Varvares says. “Those initial restrictions in response to the disease are what caused the recession, and the strength of the recovery in large part depends on how far and how successful we were in the first round of getting cases down.”

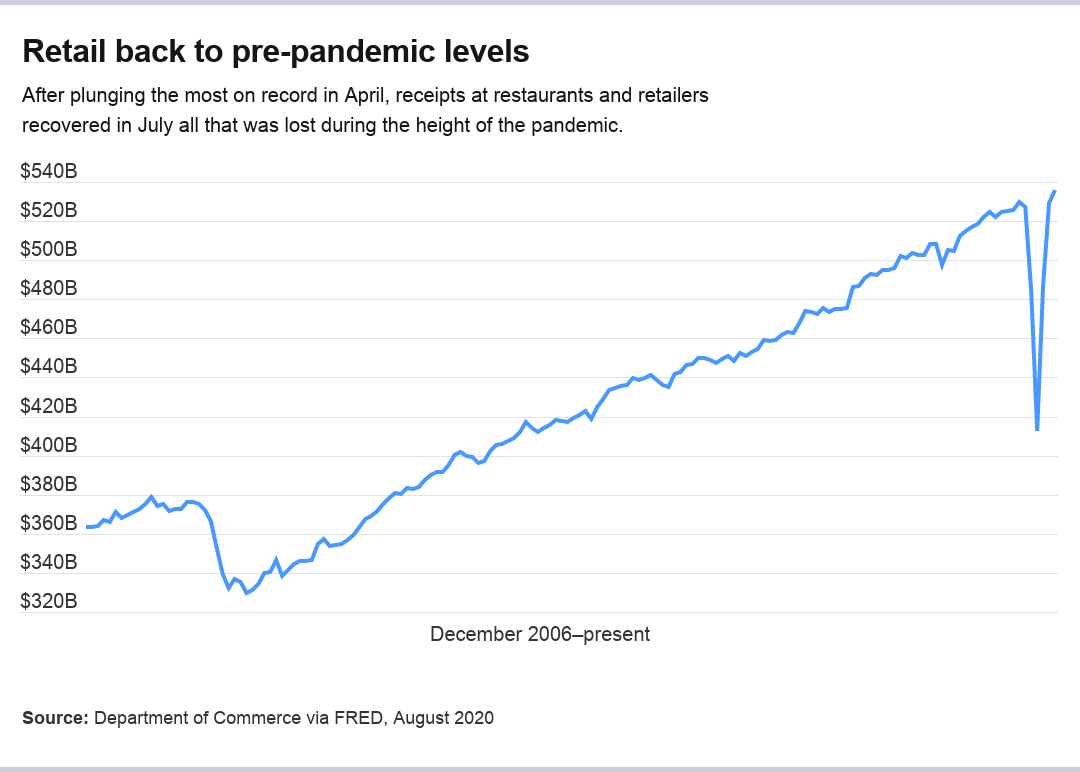

The W recession is also just as esoteric as it is rare. Some indicators lend themselves to rebounding quicker than others, especially in the case of the coronavirus crisis. Receipts at restaurants and stores, for example, have already rebounded past pre-pandemic levels, up about 2.7 percent from a year ago. Yet consumption overall is still about 3.8 percent below last year’s levels, and more than 13.5 million Americans are out of work.

Other snapshots, such as employment and the labor market, often weigh on the economy for a while after a drastic, one-time shock. Firms see lingering uncertainty and decide not to hire employees. Dramatic recessions also leave a hole in firms’ budgets, possibly causing businesses to lay off more workers even after a recession has technically ended.

Even after the Great Recession of 2007-2009 ended, joblessness still rose, peaking at 10 percent in October 2009. Unemployment also wouldn’t return to its pre-downturn low for another seven years. From the outset, that might look like a longer-lasting slump, rather than an outright rebound.

All of these mixed signals make labeling the W downturn’s two dips complicated.

“It’s sort of like throwing stones in a pond,” Varvares says. “Right when you see a new set of waves ripple off, and then you throw in another stone and the waves are intersecting. The question is, which wave dominates?”

Blame the virus for the W

When it comes to the coronavirus crisis, the W recession might as well stand for “What if?” An infinite number of forks lie ahead in the road, and there are just as many negative possibilities as there are positives.

The path the economy takes all goes back to the virus. Vaccines, medical treatments, widespread mask-wearing and social-distancing could all be an upside risk to growth. The economy could bounce back more than expected in the third and fourth quarter, boosted by a resilient consumer and strong holiday sales.

But schools reopening, the flu season and an uptick in indoor gatherings once the weather gets colder could also lead to a second wave. This year’s holiday travel season is also likely to be a shadow of its former self, weighing on the recovery, and it could also be a way of transmitting the virus again.

“People definitely respond to what they see around them,” Varvares says. “If the pullback of consumers and reimposition of containment measures is big enough, it could push you into a second downturn.”

Consumers by many measures had already started to pull back on spending long before governments imposed restrictions on activity. OpenTable data tracking the number of seated diners in the U.S., for instance, shows that dining-in dropped off in March and started plunging in double-digit territory by March 9, almost a week before California became the first state to impose a shelter-in-place order.

“If you start to see case counts begin to pick up, then you might not even need governments to impose restrictions,” says Sarah House, director and senior economist at Wells Fargo. “People might decide to hunker down again well on their own, and that’s going to put the recovery in jeopardy.”

Congress, Fed will play a vital role in how economy shapes up

The outlook also hinges on a solid monetary-policy response. Fed officials have long demonstrated that they’re willing to throw out all of the stops against the coronavirus crisis. Tools they haven’t yet broken out include yield-curve control and more specific forward guidance.

But responsibility for how the economy rebounds also rests on Capitol Hill. Lawmakers let a $600 supplemental unemployment boost expire while negotiating the second massive aid package in response to the coronavirus crisis. Though President Donald Trump circumvented a gridlocked Congress on August 8 by boosting unemployment benefits through an executive order, questions about constitutionality and implementation linger.

Economists say reinstating that joblessness aid, along with helping state and local governments and small- to medium-sized businesses, will be a crucial driver for how the economy plays out.

“In terms of the recovery in demand and activity, a lot of that is going to depend on what happens with fiscal stimulus from here,” House says.

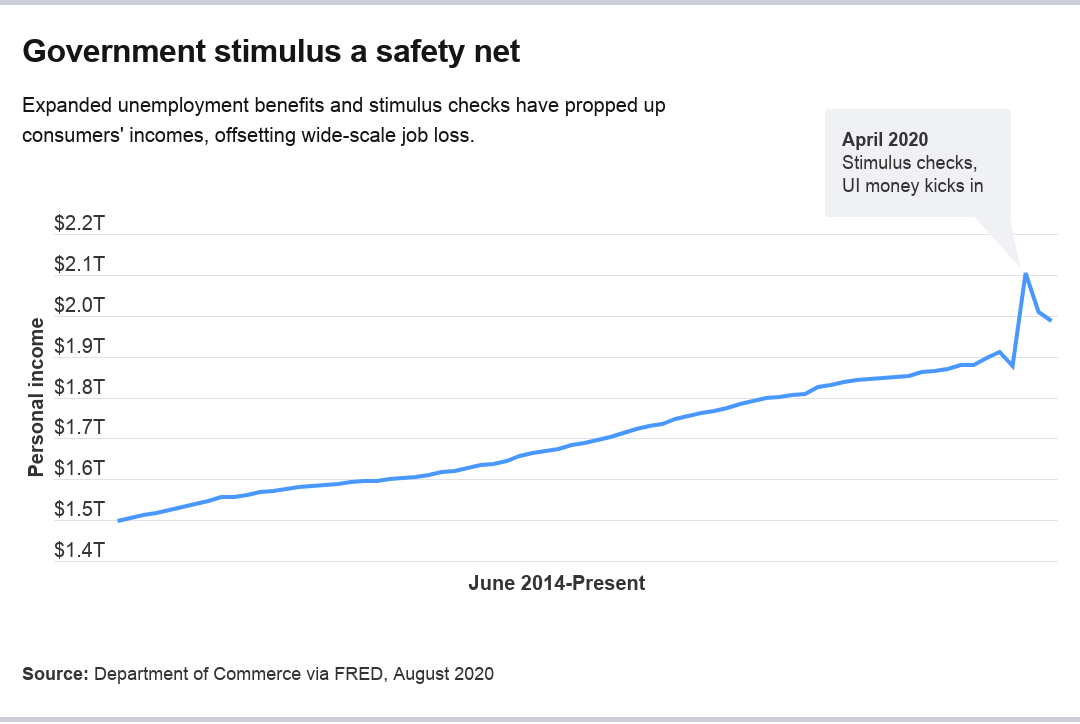

Congress’ first massive response — the CARES Act — might have played a role in the faster-than-expected rebound in hiring and spending seen across May and June. Personal income fell in March but then surged 12 percent in April, well above its pre-pandemic levels, as fiscal stimulus made its way to consumers’ wallets, according to the Department of Commerce. It’s since been on the decline, though still about 8.2 percent above where it was a year ago.

“For a lot of those folks, that was a significant amount of income,” House says. “Just the chance that it could lapse again or get reduced further, you’re going to see a lot of households very conservative in their spending.”

Forget W — long-term scarring may be more like it

But breaking into the letter game still has its fair share of risks. It’s still too soon to trace the pandemic recession’s shape, and when you try to label a crisis as unprecedented as the coronavirus crisis, you risk oversimplification.

“There’s not a good shape that describes this,” House says. “You’re going to get a much shallower trajectory in terms of where activity goes from here if you’re just looking at it in levels.”

Without another deal in sight, what’s perhaps more likely than a W-shaped recession, House says, is just an economic rebound that quickly runs out of steam. The coronavirus pandemic-induced recession was at first predicted to be one of the sharpest, yet quickest, recessions in U.S. history, but that prediction might eventually give way to long-term scarring.

Gross domestic product (GDP) — the broadest scorecard of the U.S. economy — shrank by 31.7 percent on an annualized basis in the second quarter of 2020, according to the Department of Commerce’s most recent release. The financial system is expected to rebound by 29.9 percent in the third quarter, according to the Atlanta Fed’s widely watched GDPNow tracker. Meanwhile, about 52 percent of pandemic-related job cuts have returned, and nearly 3.7 million workers have dropped out of the labor force.

If you’re going off of shapes, that might mean the economy looks something like a flattened “swoosh.”

“This could be technically a very short recession if you just consider the time between when activity declines and bottoms from peak to trough,” House says. “In many ways, this was only a two month-recession, but the recovery is going to be much longer, and for many, it’s going to feel like we’re still in a recession for a very long time.”

How you should prepare for another downturn

From a personal finance perspective, preparing for even the remote possibility of a W-shaped downturn is wise — though it might seem daunting, given how many Americans’ wallets haven’t recovered from the first dip, which most likely happened in March.

“What’s been tricky with a W-shaped recession is, a lot of people thought things were going back to normal. Things are opening back up, then all of a sudden, things aren’t returning to the way they were,” says Tyler Reeves, CFP, founder of Plimsoll Financial Planning who is based in Alabama. “The big thing that I have been stressing is the importance of having resiliency built around your financial plan.”

In many instances, that means taking the same steps you took to prepare for the first leg of the W-shaped recession:

- Keep cash on hand: Experts recommend storing around six to nine months’ worth of expenses in a liquid, accessible savings account. “Cash is king in situations like this,” Reeves says.

- Cut back on expenses: Find ways to trim your budget, limiting your discretionary purchases and eliminating any monthly bills that you could go a few months without.

- Find opportunities to lower your interest rates: Refinancing your mortgage could potentially shave hundreds of dollars off your monthly payment, while a balance transfer card could trim your interest rate if you’re carrying around high-cost credit card debt.

- Avoid payday loans, credit card borrowing if you still need cash: A personal loan, or even tapping into a retirement account, would be a better option if you’re cash-strapped rather than borrowing from a high-interest payday lender or running up the balance on a credit card.

- If you need more funds, don’t be afraid to pull back for now on your retirement contributions: “If you are in a situation where your income is rocky or you feel that you’re in an industry or a profession where you could lose your job, it’s OK not to save money into retirement accounts,” Reeves says. “It’s OK not to put money into your college funds right now. It’s much better to build up that cash reserve and have it on hand, than it is to go to another place to get that cash, like a credit card.”

Learn more:

- 13 steps to take if you’ve lost your job due to the coronavirus crisis

- Coronavirus pushes home sales off a cliff. When will they recover?

- Stimulus checks: What consumers should consider doing with the money

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.