All the ways a president can (and can’t) influence the Federal Reserve

The Federal Reserve has gone full throttle in its fight against the hottest price surge in four decades — a policy plan that U.S. central bankers haven’t often been given the authority to do without some attempt at political interference.

In fact, the Fed’s failure to contain inflation in the 1970s traces back to the political forces that shaped the Fed chairs in charge, suggests former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke in his May book “21st Century Monetary Policy.”

“Martin, my boys are dying in Vietnam, and you won’t print the money I need,” President Lyndon B. Johnson reportedly told then-Fed Chair William McChesney Martin Jr. at his Texas ranch after the central bank announced a half-point increase to its key discount rate over inflation fears, Bernanke writes. White House tapes, meanwhile, reveal President Richard Nixon frequently appealing to Fed Chair Arthur Burns’ Republican-party ties to clear the runway for more easy-money policies, with one call going as far as urging the Fed chair not to make any policy decisions that could “hurt us” in the November 1972 election.

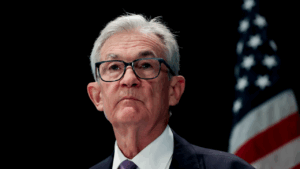

Fed watchers may even remember everything President Donald Trump had to say about the Fed — calling it “the biggest threat” to the U.S. economy — and the chair whom he elevated, Jerome Powell — equating him to a golfer “who doesn’t know how to putt” and an enemy.

President Joe Biden has suggested he’s trying not to repeat history. “My predecessor demeaned the Fed, and past presidents have sought to influence its decisions inappropriately during periods of elevated inflation,” Biden said in May after a meeting with Powell. “I won’t do this.”

All of it’s reviving a question that’s been around as long as the U.S. central bank itself: How does the president influence the Fed?

What power does the president have over the Federal Reserve?

- A president can appoint – and technically fire – the Fed chair

- A president does appoint the majority of voting officials

- But a president is not the sole arbiter of who takes those seats

- A president can voice his concerns and participate in the conversation – and Trump’s not the only one who’s done it

- But a president cannot bar the Fed from raising interest rates

1. A president can appoint – and technically fire – the Fed chair

Presidents nominate a Fed governor to the post of chief central banker— and experts say they could be the ones to also kick them out, though there isn’t any precedent.

Section 10 of the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 specifies that Fed governors can be “sooner removed for cause by the president.” The Fed chair is also considered a governor, meaning this provision likely extends to him or her as well, says Sarah Binder, professor of political science at George Washington University, who studies the Fed’s relationship with Congress.

But what constitutes a “cause,” is not exactly clear, though it likely doesn’t include a disagreement on the direction of interest rates.

“Just because the president doesn’t agree with your policy choices doesn’t mean he can dismiss you,” Binder says.

The Truman administration forced Thomas McCabe to resign after about three years as Fed chair, appointing William McChesney Martin Jr. in his place, but no president has attempted to fire a Fed chief before using the “cause” provision.

Yet, if a president decided to kickstart a legal battle to oust the chief U.S. central banker, the courts will likely look to similar roles for illumination, such as the chairman of the Federal Trade Commission, says Pete Earle, a research fellow at the American Institute for Economic Research.

The legal standards surrounding the FTC chairman say this official can only be removed for “inefficiency, neglect of duty or malfeasance in office.” Applying that to the Fed chair, however, might be a little more complicated, Earle says.

“Is raising rates a neglect of duty?” Earle says. “I don’t see any court arguing that, especially when they’re hired for their policy and their academic expertise. The Fed is charged with this duty of adjusting rates as it sees fit.”

Fed Chairs also don’t have limits as to how many four-year terms they can serve. Alan Greenspan, for example, was Fed chair for nearly 18.5 years. If a president chose to appoint someone else, the Fed chair could remain on the board as a governor. They could also, however, decide to leave the Fed completely — as did former Fed Chair Janet Yellen when Powell was sworn in.

2. A president does appoint the majority of voting officials

While a president would find ousting a Fed chief particularly difficult, there are still other ways in which the chief executive can influence the Fed — mainly by choosing whom to elevate for the Fed’s board of governors.

Of the 19 total Fed officials, 12 at any given time serve on the Fed’s rate-setting Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), seven of which are the Fed’s board of governors. Those governors serve a maximum of 14 years, pending a fresh nomination from the president and confirmation from the Senate at the end of each term. They also have a vote on policy at all times, unlike the regional reserve bank presidents, who rotate off on an annual basis (with the exception of the New York Fed).

For the first time since 2013, the Fed’s board of governors is fully staffed. They include Obama-era appointees Lael Brainard and Powell as well as Trump picks Michelle Bowman and Christopher Waller. President Joe Biden selected all others: Michael Barr, Lisa Cook and Phillip Jefferson.

Presidents are often steered by their parties to select someone who aligns with their economic views. In fact, many presidents appoint members of their Council of Economic Advisors or Treasury staff to posts at the Fed.

President Harry Truman appointed Martin to the Fed board with the hopes that he would “serve the president’s political ends” after helping negotiate a key accord between the Treasury and the Fed in 1951 as an assistant secretary at the Department, Bernanke writes. Burns was later appointed to become Fed chair after establishing trust with Nixon during his vice presidency with Dwight D. Eisenhower, who picked Burns to be chair of the Council of Economic Advisers, Bernanke writes. Former Fed Chair Janet Yellen, for example, even left the Fed board to chair President Bill Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers.

Experts and former FOMC members who’ve been inside the room during rate decisions have said there’s no room at the Fed for political views. All of that suggests, politics stay out of the conversation when officials are deciding what to do with interest rates.

3. But a president is not the sole arbiter of who takes those seats

Just because the president picks those who occupy seats on the board doesn’t mean they ultimately make it through. The Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs confirms each nomination, while others simply don’t make it through the process.

Trump, for example, nominated Marvin Goodfriend, who was a professor of economics at Carnegie Mellon University, but he was never confirmed. He died of cancer in December 2019. Nellie Liang, a Brookings Institution fellow, withdrew her name from consideration after facing Republican and Wall Street opposition. Meanwhile, Biden’s pick Sarah Bloom Raskin took her name out of the hat for the Fed’s vice chair for supervision after senators on both party lines said they wouldn’t vote for her.

Also insulating the Fed from presidential influence are the 12 regional Fed banks across the country. Presidents do not control who runs them. Instead, directors form a search committee and hire a firm to identify “a broad, diverse, highly qualified candidate pool,” according to the Federal Reserve. The Fed’s board of governors then approves the final pick.

4. A president isn’t barred from voicing his concerns and participating in the conversation

Americans might remember Trump’s comments on the Fed throughout his presidency. Amid the Fed’s four 2018 rate hikes, Trump said the Fed was “going loco” with interest rate hikes and that “he’s not the least bit happy” with his pick to lead the central bank.

Nothing specifically prevents a president from voicing his concerns, according to AIER’s Earle. Greenspan himself even noted receiving “innumerable notes, pledges, requests, et cetera to lower rates.” He stated: “I do not recall a single instance where somebody in the political realm said we need to raise rates, they’re too low,” he said in an October 2018 CNBC interview.

It is, however, more of an unspoken rule to keep your opinions about monetary policy tight-lipped — typically not commenting on Fed policy as publicly as Trump did.

Truman along with Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush have all explicitly commented on the direction of interest rates, according to Earle’s research. Truman in a later encounter with his Fed chair appointee Martin called him a “traitor.”

In a phone call with then-Fed chair Arthur Burns, Richard Nixon said, “Independent! You get it [the money supply] up. I don’t want any more nasty letters from people about it. OK?” Another conversation urged Burns not to make any policy decisions that could “hurt us” in the November 1972 election.

Presidents, however, tend to weigh in on monetary policy when the economy is doing poorly, Binder says.

5. But a president cannot officially bar the Fed from raising or lowering interest rates

When experts say the Fed is independent, that’s mostly because the central bank has the power to raise, lower or maintain interest rates without approval from the legislative or executive branches. This means that there’s nothing a president can really do to prevent the Fed from raising rates.

Still, that hasn’t stopped people from fearing that the president’s comments do have some sort of influence over policy, Binder says.

“There is no more salient political actor in the United States,” she says. “Nobody can compete with the level and spotlight of media attention.”

For example, Powell and former Fed Vice Chair Richard Clarida met with President Donald Trump and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin at the White House for dinner back on Feb. 4, 2020. Immediately afterward, they issued a statement, likely to keep people from panicking about political interference, Binder says.

A public statement also accompanied Biden’s meeting with Powell in May.

Rethinking what it means to be independent: The Fed is nonpartisan with political roots

The irony is that the Fed’s independence is granted by the very people who have the power to take it away, points out Irwin Morris, a professor at the School of Public and International Affairs at North Carolina State University.

It’s not as if Congress has left the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 unchanged, and sometimes major economic events lead Congress to adjust the Fed’s scope. They most notably revised it in the aftermath of the Great Recession, to reflect the Fed’s new regulatory and supervisory responsibilities. In 1942, for example, the Fed had capped both short- and long-term interest rates to lower how much the government was spending to finance war debts, where it stayed until 1951 under the Treasury-Federal Reserve Accord, despite inflation fears.

Stripping the Fed of its powers, however, would not be easy.

“There would be political and economic costs of a drastic change of the nature of the institution,” Morris says. “Everyone would have to be on board, and how many policymaking initiatives have had that sort of overwhelming support recently? Not many.”

For this reason, it’s best to rethink Fed independence, Binder says. Just because an institution is nonpartisan, doesn’t mean it’s apolitical, she says.

“Central banks claim they’re independent, even though we can think about the ways in which they are sitting in the middle of the political system,” Binder says.

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.