Fed hikes interest rates by three-quarters of a point to combat decades-high inflation

For the first time in almost 28 years, the Federal Reserve on Wednesday lifted interest rates by three quarters of a percentage point, a historic move that kicks policymakers’ fight against stubbornly and painfully elevated inflation into high gear — and also raises the risk of kickstarting a recession.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) set 1.5-1.75 percent as the new target range for the federal funds rate — a key benchmark borrowing rate that acts as a lever for borrowing rates from credit cards to car loans as well as yields on certificates of deposit (CDs) and savings accounts. The move officially takes borrowing costs back to pre-pandemic levels from 2019.

Fed policymakers show no signs of stopping there. Fresh forecasts also released with the June decision show projections for a 3.25-3.5 percent federal funds rate by the end of 2022, the highest since 2008. If this comes to fruition, it would mean the most rate hikes in a single year since the 1980s — three of them likely higher than the traditional quarter-point increases.

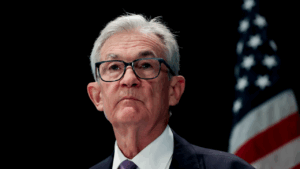

“I do not expect moves of this size to be common,” said Fed Chair Jerome Powell at a post-meeting press conference, referring to the 0.75 percentage point move. “Either a 50 basis points or 75 basis points increase seems most likely at our next meeting.”

- Fed raises rates to target range of 1.5-1.75 percent and forecasts a 3.25-3.5 percent fed funds rate by year-end.

- Officials project 5.2 percent inflation for 2022, up from 4.3 percent.

- Policymakers expect joblessness in 2022 to rise slightly to 3.7 percent.

- Kansas City Fed President Esther George dissented, preferring a half-point hike over a three-quarter-point increase.

What it means for: Mortgage rates | Savers | Borrowers | Investors

The decision paints a troubling picture about how much policymakers must slow the economy to stamp out the highest price pressures in 40 years. Up until last Friday, officials were broadly expected to raise interest rates by half a point, keeping the larger, 75-basis-point hike off the table. That was until prices in May unexpectedly accelerated to a fresh high of 8.6 percent and other data showed signs that central bankers’ credibility with inflation was slipping — perhaps even more troubling.

The larger, more aggressive move might help the Fed achieve what it hopes will be a “soft” — or at least “softish” — landing for the U.S. economy, meaning a gradual cooling of inflation that doesn’t cause a dramatic spike in unemployment or a drastic plunge in economic activity. But the higher rates climb, the Fed risks slamming the brakes on the financial system too hard and too fast.

Stocks and bonds were caught in the middle of a sharp sell-off in the days leading up to the decision, with the S&P 500 officially entering bear-market territory and the 10-year Treasury yield rising to a level not seen since 2011. Consumers are sure to feel that sudden and quick tightening in their wallets, likely attributable to the 30-year mortgage rate’s ascent to more than 6 percent, now up around 3 percentage points since December.

“The old maxim ‘desperate times call for desperate measures’ appears to have come into play with this latest rate move,” says Mark Hamrick, Bankrate senior economic analyst and Washington bureau chief. “The Fed’s goal, and literally its mandate, is to get an upper hand on inflation, amid the widespread perception, and the probable reality, that the central bank has been behind the curve with monetary policy.”

The Fed’s rate hike: What it means for you

Mortgages and refinance rates

So far this year, mortgage rates have looked like the only direction they’re heading is up, and would-be homebuyers are feeling the pinch. Activity in the housing market is showing signs of cooling, with mortgage applications down 76 percent from a year ago, according to weekly data from the Mortgage Bankers Association. Yet, home prices have shown no signs of noticeably slowing from the record highs in the first quarter of 2022.

Higher rates are creating all types of new affordability challenges. Affording a $316,000 home with mortgage rates 6 percent is the equivalent of paying for a $450,000 home with a 3 percent mortgage rate, according to an analysis from Ali Wolf, chief economist at Zonda, a housing market research platform.

As always, those with a fixed-rate mortgage won’t feel any impact from the Fed’s rate hike. But the historically low mortgage rates that prevailed during the pandemic — and even in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis — look like they’re all but in the rearview mirror. That zaps away the same refinance opportunities from 2021 and 2020, though homeowners might still be able to find a better deal if they shop around.

The same goes for would-be homebuyers as a whole. Some lenders might offer lower rates than others to compete.

But where mortgage rates head from here is just as uncertain as the outlook itself. If investors start to fear that an economic slowdown could be on the horizon, bond yields could eventually start to fall again — meaning lower mortgage rates. But an economic slowdown could bring challenges in itself that might outweigh the benefits of low mortgage rates, from higher joblessness to a bumpier stock market.

Borrowers

Consumers will be in a much better position in a rising-rate environment if they can eliminate any variable-rate or high-cost debt. The best course of action will likely be to consider refinancing into a fixed-rate loan, as well as taking advantage of a balance transfer card should it offer low promotional rates.

Credit card rates follow the prime rate — which typically holds 3 percentage points above the fed funds rate. Not only that, but issuers typically charge borrowers a margin on top of the prime rate, so some consumers could have higher borrowing rates than others depending on their credit history.

Savers

Yields are on the rise, particularly at nontraditional online banks, but savers are still waiting for their time to shine: Even with yields on the rise, they’re unlikely to eclipse the 40-year high inflation rate. Not only that, but the national average interest rate for savings accounts is still a next-to-nothing 0.07 percent, according to Bankrate data.

But don’t let today’s high-inflationary environment keep you from saving. In fact, the changing landscape only underscores the importance of saving even more, especially if a downturn is possible. Consumers will get the most bang for their buck by shopping around for the best account on the market that also fits their financial needs. In other words, don’t sacrifice yield-chasing for liquidity, particularly if your savings account is housing your rainy-day fund.

Investors

The days of zero rates have come to an end — and it’s raining on investors’ parade. Asset prices have been volatile, choppy and painful, particularly for investors who took on riskier investments when money was cheap. While the S&P 500 only recently entered bear market territory, the NASDAQ reached it on March 7.

The ride could only get bumpier from here as investors process what it means to have a much more aggressive Fed than was expected even just a week ago.

But even though the economy is fraught with risks, don’t let recent volatility keep you from investing for longer-term goals such as retirement. And better yet, see the latest downdraft in the market as a significant buying opportunity for the long-run. Stocks are now heavily discounted from the record highs of 2021, although markets remain highly uncertain for the time being.

Fed’s next moves depend on inflation, with stagflation concerns rising

The bulk of the Fed’s tightening is forecasted to happen this year, officials’ projections also show. By the end of 2023, officials penciled in a 3.5-3.75 percent federal funds rate, just a quarter point higher than where they’re projected to take rates by December.

Notably, that’s a full percentage point above officials’ estimates of the so-called “neutral rate of interest” — meaning the point at which borrowing costs start to officially restrict economic growth.

“The worst mistake we can make would be to fail, which is not an option,” Powell said. “We have to restore price stability.”

Higher rates could increase joblessness

After that, all but four officials are expecting to cut borrowing costs in 2024, with the median estimate for the year back at 3.25-3.5 percent. Six officials, however, see even bigger cuts — with the lowest projection calling for a 2-2.25 percent fed funds rate.

That’s likely because policymakers are expecting there to be some pain in the labor market as rates start to rise. Officials revised their projections for the unemployment rate higher across the Summary of Economic Projections’ entire two-year period, penciling in a 3.7 percent rate for 2022, a 3.9 percent rate for 2023 and a 4.1 percent rate for 2024. Just 3.6 percent of workers were jobless in May, near a half-century low, according to the Department of Labor.

Although that forecast is off in the distance, it still rings alarm bells for a downturn. A popular economic indicator — known as the Sahm rule — suggests that a recession has begun once unemployment has risen half a percentage point from its 12-month low.

Powell, however, stopped short of saying policymakers see a recession on the horizon, adding that a 4.1 percent unemployment rate is still low by historical standards.

“We’re not trying to induce a recession now, let’s be clear about that,” Powell said. “We don’t seek to put people out of work. We never think too many people are working, but we can’t have the kind of labor market we want without price stability.”

Inflation to remain elevated through 2024

Inflation, however, is still likely to remain above the Fed’s 2 percent objective through 2024, even with interest rates expected to rise almost a full percentage point higher by the end of next year than originally forecasted in March. The Fed expects inflation to hold more than two times above its preferred level of 2 percent in 2022, with officials now expecting 5.2 percent headline inflation and 4.2 percent price pressures when stripping out food and energy. After that, headline inflation is expected to cool to 2.2 percent by 2024.

“A 4.1 percent unemployment rate with inflation well on its way to 2 percent, I think that would be a successful outcome,” Powell added.

At the same time, the U.S. economy is expected to grow at a dramatically slower pace — a total 4.2 percentage points slower over the next two years than it previously forecasted in March. By the end of this year, the financial system is projected to expand by 1.7 percent. A separate estimate by the Atlanta Fed puts second quarter growth at 0 percent.

With inflation high, unemployment rising and growth slowing, nervous Fed watchers are worried it could be the recipe for another period known as “stagflation,” which last posed a threat to the U.S. economy in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Experts, however, say front-loading rate hikes might give the Fed more flexibility down the road.

“We do expect inflation to decelerate but the timing may be pushed out on the calendar,” says Luke Tilley, chief economist at Wilmington Trust. “The more it gets pushed out, the more aggressive the Fed needs to be, raising the risk that a softish landing turns into a rockyish one.”

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.