The Fed’s latest meeting wasn’t just about interest rates. Here’s why you shouldn’t overlook its balance sheet announcement

Key takeaways

- The Federal Reserve announced it would keep interest rates at a 23-year high after its May gathering, but also announced plans to shrink its massive $7.4 trillion balance sheet at a slower pace.

- The Fed's balance sheet ultimately impacts the money supply and availability of credit in the economy.

- Fed officials are hoping to avoid the risk of shrinking the money supply too much, which could cause market volatility and make their inflation fight more difficult.

When the Federal Reserve announced that it would keep interest rates at a 23-year high after its May gathering, another consequential policy decision for consumers may have flown under the radar.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) also announced that it plans to shrink its massive $7.4 trillion balance sheet at a slower pace — a step that isn’t as high-profile as U.S. central bankers’ interest rate moves but important for Americans’ finances nonetheless.

The Fed’s balance sheet ultimately ends up impacting the money supply and availability of credit in the economy. U.S. central bankers also use their bond portfolio to influence the longer-term interest rates that they don’t typically control, such as the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage and the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield.

But perhaps the most important reason the upcoming moves are important: Fed officials are hoping to avoid the risk of shrinking the money supply too much. Taking the process too far risks spurring unnecessary market volatility that could make the Fed’s inflation fight even harder. One such case from 2019 caused interest rates to spike in the market for short-term repurchase agreements — prompting Fed officials to reverse course and start growing banks’ reserves again.

If they’re worried that liquidity is becoming a little strained, then that argues for scaling back the pace of runoff. You dont know you’ve gone too far until you’ve gone too far.— Greg McBride, Bankrate Chief Financial Analyst

Key takeaways on what the Fed is changing with its balance sheet

- Starting June 1, policymakers are going to let up to $25 billion of Treasury securities roll off their balance sheet each month at maturity.

- Between September 2022 and May 2024, officials were shrinking their Treasury holdings by up to $60 billion a month, meaning officials now plan to cut the process by more than half.

- Fed officials are going to continue letting up to $35 billion of mortgage-backed securities roll off their books each month at maturity.

- Current balance sheet size, as of May 2: $7.4 trillion

- Balance sheet peak: $8.97 trillion

- How much balance sheet has shrunk: $1.6 trillion

The Fed’s balance sheet has been a lesser-known part of its inflation fight

The Fed’s latest balance sheet announcement is almost four years in the making, tracing back to the start of the devastating coronavirus pandemic-induced recession. As the gears of commerce ground to a near halt, Fed officials implemented their biggest bond-buying program on record, purchasing almost $5 trillion total of securities to give the economy more juice.

When the Fed grows its balance sheet, it essentially ends up printing money — albeit digitally. The Fed purchases an asset, then credits banks’ reserve accounts with cash in equal value. The financial system thus becomes awash with more liquidity, hopefully spurring greater lending among financial firms.

Consumers have those moves to thank for the historically cheap mortgage rates of the pandemic era. The 30-year fixed rate fell to a record low of 2.93 percent in 2021, Bankrate’s data shows.

But the Fed’s ultra-stimulative policies were never intended to last forever — especially as consumer prices barreled to new 40-year highs throughout 2022. Starting in June 2022, Fed officials began letting up to $47.5 billion worth of bonds roll off their portfolio at maturity each month. Then, by the following September, they scaled up those monthly caps to $95 billion — where they’ve held since.

What is the Fed’s balance sheet?

Find out more about this behind-the-scenes Fed policy move that has major implications for your wallet.

Read moreAs the biggest bond buyer in the marketplace started stepping away, the Fed’s balance sheet reversal had the opposite effect on mortgage rates.

Mortgage rates surged faster than experts and prospective homebuyers have ever seen. Between the end of 2021 and the beginning of the Fed’s balance-sheet drawdown, mortgage rates climbed a full 2 percentage points, hitting 5.27 percent by June 1, 2022, Bankrate data shows. By September 2022, as the Fed forged ahead full-force, mortgage rates had more than doubled from their year-end 2021 levels, hitting 6.73 percent.

The 30-year fixed-rate mortgage remains elevated even today, now holding above 7 percent for three consecutive months, according to Bankrate’s national survey of lenders

One indication that the Fed could be to blame for the surge in mortgage rates: the wide spread between the 10-year Treasury rate and 30-year fixed-rate mortgage. Since February 2022, it’s been holding above its typical pre-pandemic level by almost a percentage point — or more.

“If we were operating with historic spreads, the 30-year fixed would be 6.4 percent today instead of 7.3 percent,” McBride says. “The less Treasury debt that rolls off the Fed’s balance sheet, the less debt that has to be absorbed by the market. This could help keep long-term Treasury yields in check after heady increases thus far in 2024.”

Treasury yields — and mortgage rates — might not surge as much

But the Fed’s balance sheet isn’t the only factor impacting the key yields that dictate the 30-year fixed mortgage rate.

Stubborn inflation is keeping a floor on how low yields can go. As investors — and Fed officials themselves — started losing hope that price pressures are on an assured path to 2 percent, the 10-year Treasury yield has risen almost a percentage point since December 2023.

The supply of debt is also a factor. So far in fiscal year 2024, the government has been running a $1.1 trillion total deficit, data from the Bipartisan Policy Center shows. That new debt has to find new buyers. And just as the Fed started backing away from the bond market, Congress gave bond investors a debt-default scare in summer 2023. Lawmakers ended up reaching a deal to raise the federal borrowing limit, but it didn’t stop rating agency Fitch from nixing the U.S. of its top AAA credit rating.

“It’s like what we’re seeing on the inflation front: The hits just keep on coming,” McBride says. “The trajectory on federal debt issuance is unsustainable, and it’s getting worse. That is commanding the attention and concern of bond investors.”

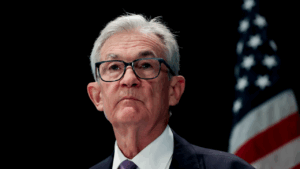

Fed officials, however, don’t like surprising markets. Since the Fed’s March rate-setting gathering, Fed Chair Jerome Powell has been preparing investors for a balance sheet announcement. Many experts, however, were surprised by just how much Fed officials decided to cut their monthly Treasury caps.

Still, the highest borrowing rates in over a decade aren’t going anywhere, though their ascent might slow, now that the Fed isn’t shrinking the availability of credit in the economy as much.

“It’s reasonable to assume that the spread and, therefore, mortgage rates will retreat later in the year if the Fed decides to cut rates and provide investors with more certainty,” says Odeta Kushi, deputy chief economist for First American Financial Corp. “However, a higher-for-longer stance will likely prevent mortgage rates from declining meaningfully.”

Fed’s shifting balance sheet is more about preventing market disruptions than teeing up rate cuts

But don’t conflate rate cuts with the Fed’s balance sheet announcement. Rather, Fed officials are mainly deciding to slow the process sooner than later to prevent disrupting financial markets as much as they did in 2019, when it looked like Fed officials might have shrunk banks’ reserves too much.

Turmoil mainly impacted the repurchase agreement, or “repo,” market. In this complicated corner of the financial system — often equated to the world’s largest pawn shop — trillions of dollars worth of debt are traded for cash each day. The gears of commerce rely on it functioning smoothly, with firms utilizing it to finance short-term funding needs. A credit crunch here can also end up impacting the borrowing costs consumers pay.

During the 2019 snafu that caused the repo market to seize up, rates surged as high as 9 percent during one day of trading, even though the Fed’s key federal funds rate was holding in a target range of 2-2.25 percent at the time, a Cleveland Fed analysis found.

“It really is to ensure that the process of shrinking the balance sheet down to where we want to get it, is a smooth one and doesn’t wind up with financial market turmoil the way it did the last time we did this,” Powell said at the Fed’s May post-meeting press conference, referring to the Fed’s balance sheet announcement.

Powell has also suggested that those disruptions can make the Fed’s inflation-fighting goals harder, too. Back in 2019, the Fed ended up having to inject cash into the market to keep interest rates in line with their desired target range — factors that ultimately ended up causing the balance sheet to grow again. At the time, a similar normalization process was already underway, with Fed officials attempting to shrink banks’ reserves after rapidly expanding them in the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008.

“They’re smart about wanting to avoid any type of hiccups,” says Ben Bakkum, CFA, senior investment strategist at Betterment. “It wouldn’t be what they would want to be doing — to have to increase the size of the balance sheet because of the mechanics and the plumbing of the financial system.”

Bottom line

Just because the Fed is slowing down the process now, also doesn’t mean the balance sheet will stop shrinking. Much like a car that slows down as it approaches its exit on the interstate, officials will instead just try to approach their destination much more gradually.

“Normalizing the balance sheet more slowly can actually help get to a more efficient balance sheet in the long run by smoothing redistribution and reducing the likelihood that we’d have to stop prematurely,” said Dallas Fed President Lorie Logan, who was at the helm of the last normalization process while working at the New York Fed, during a January speech.

But no matter what, consumers are unlikely to ever see the Fed’s balance sheet — or banks’ reserves — return to the levels they were in the past.

“It’s Hotel California: You can check in but never check out,” McBride says. “When you focus on downsizing it, you only downsize it a little bit — and the next crisis, it gets bigger and bigger. The next 50 percent change in the size of the Fed’s balance sheet is going to be larger, not smaller.”

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.