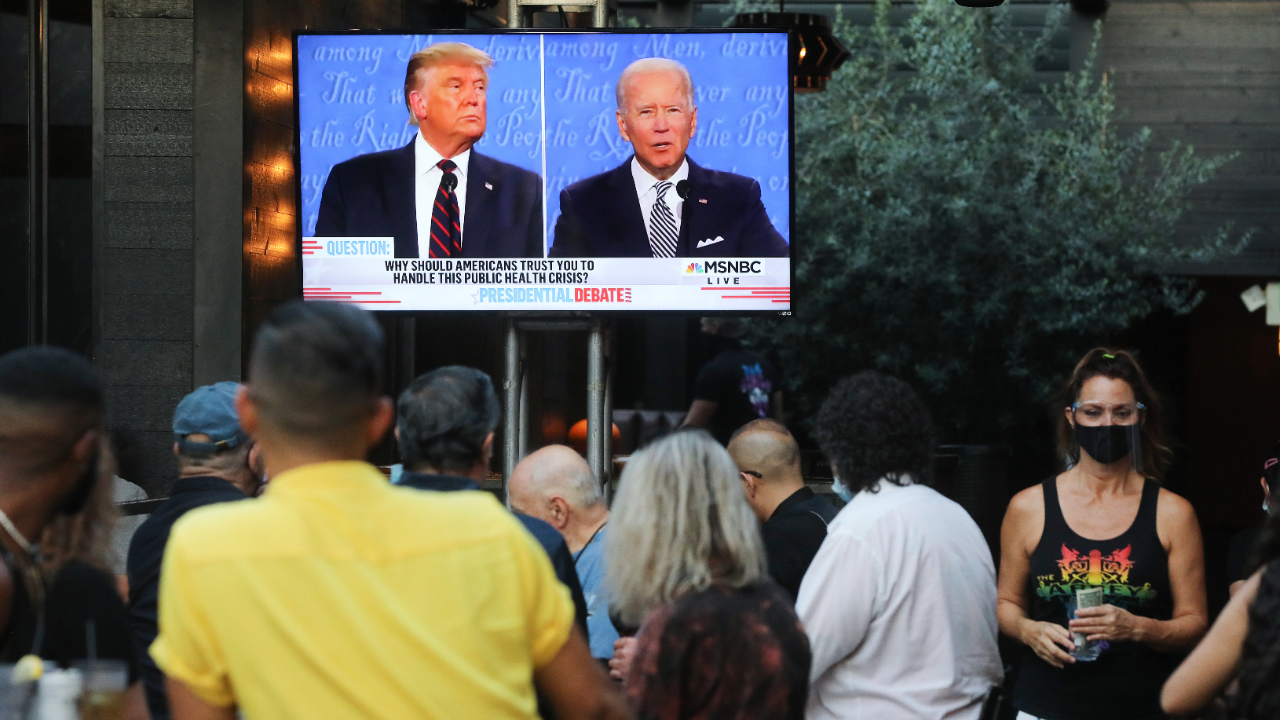

Biden vs. Trump on creating jobs: Here’s how they plan to battle coronavirus-driven recession

Whether it’s President Donald Trump or former Vice President Joe Biden, either candidate will have to grapple with an ongoing joblessness crisis when he gets to the Oval Office.

Employers brought back jobs a lot quicker than experts initially expected when the coronavirus crisis first took hold. Shutdowns from the pandemic wiped away almost 15 percent of all jobs in the U.S. economy, higher than the sum of all positions lost during the Great Recession from 2007-2009. More than half have been recovered, yet momentum is slowing, and Federal Reserve officials are spelling out concerns that bringing back the rest will only get harder.

Here’s everything you need to know about how Trump or Biden plan to spur job creation if they’re elected, including how effective those policies might be and what it means for you.

Where do Biden and Trump stand on job creation?

- Trump: Tax cuts, deregulation, possible infrastructure spending

- Biden: Tax hikes on corporations and wealthy, infrastructure plan, government-subsidized testing

- Tax hikes could weigh on economy, but tax cuts might not make it through to your wallet

- The coronavirus crisis puts future policy changes in question

Trump: Tax cuts and deregulation as an economic booster shot

The Republican incumbent is promising to create 10 million new jobs in 10 months and 1 million new small businesses in a second-term agenda described on his campaign’s website. While the plan lacks specifics, Trump will likely move to cut corporate and payroll taxes and providing firms with tax credits to get the gears of the economy moving again.

For Americans, that means Trump will most likely stick to his status quo.

Trump’s prevailing argument for the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) was that it would spur more economic growth, which would create jobs, while also boosting wages as corporations reallocate their extra cash. For companies, the TCJA cut corporate taxes from 35 percent to 21 percent, and among other cheered provisions, allowed for a 100 percent capital expenditures deduction.

Trump has already been vocal about also reducing payroll taxes if he’s reelected in November. Those levies are paid specifically by employers to fund entitlement programs such as Social Security and Medicare. Also pursued might be marginally reducing the corporate rate tax down to 20 percent.

When it comes to direct spending to combat the coronavirus crisis, Republicans in Congress have been hesitant about throwing too much money, given the faster-than-expected pace of the rebound. A second-term Trump administration might move away from direct virus relief and instead turn to more traditional ways of boosting growth, such as infrastructure spending. Trump back in June reportedly directed his administration to create a $1 trillion stimulus plan, according to Bloomberg and Reuters. Most of that money would go toward building roads and bridges and setting aside funds for 5G wireless and rural wireless broadband, but analysts cautioned that it might not come to fruition with Congress divided.

Similar to the Great Depression-era federal initiatives of the 1930s, infrastructure spending has long been a method for which Washington policymakers seek to prod the economy, though the Trump administration doesn’t directly estimate how many jobs the package would create.

Biden: Increased government spending, then targeted tax hikes for manufacturing and green energy proposals

Democratic nominee Biden might have the complete opposite point of view when it comes to kick starting job growth. He is proposing raising taxes to generate enough revenue to fund a $2 trillion infrastructure plan and other investments.

Biden has promised not to increase taxes on individuals who earn less than $400,000 a year; instead, he is setting his sights on boosting levies on major corporations and the wealthy. Those extra funds could generate about $3.1 trillion in revenue, according to the Tax Foundation. These funds would be reallocated into new spending proposals, such as health care and education, as well as other hopeful job-creating investments.

Corporations would mostly see a three-part tax policy adjustment. Biden proposes a 15 percent minimum “book” profit tax proposal on companies that earn more than $100 million in revenue. He also wants to increase the corporate tax rate from 21 percent to 28 percent, and employers might have to pay payroll taxes on wages above $400,000 a year.

While no dollar amount is provided, Biden wants to expand the availability of government-funded testing, which experts say might lead to more targeted lockdowns, preventing another round of nationwide lockdowns if cases spiked again.

When it comes to Biden’s $2 trillion infrastructure plan, the campaign estimates that would create 1 million new jobs in the auto industry by expanding factory floors, 250,000 jobs for plugging abandoned oil and natural gas wells, and another million jobs for updating homes, transit and buildings to be environmentally friendly and sustainable. While details are scarce, Biden also unveiled plans for a $700 billion manufacturing program to create what he estimates could be 5 million jobs by investing in American-made products. Manufacturing firms would also receive a tax credit, for instance, if they expand their U.S. operations and hire more workers.

“Both of them are talking about infrastructure spending, which tends to have a good multiplier effect,” says Steve Skancke, chief economic advisor at Keel Point Capital who worked on the economic policy team at the Treasury Department during the Nixon, Ford, Carter and Reagan administrations.

Tax hikes or tax cuts? One might weigh on the economy, but the other might not help workers

The effectiveness of tax hikes versus tax cuts isn’t always easy to track. All else equal, tax cuts could spur growth, while tax hikes would weigh on growth. But that never actually happens in the real world.

“It’s never easy to do a one-to-one connection,” Skancke says. With higher tax rates, “there’s just less money to reinvest in new enterprises and opportunities that arise in a recovering economy. So by definition, you’re going to have a slower rate of growth. Exactly how and where it pops up is always a little bit difficult to point out.”

The independent policy nonprofit Tax Foundation estimates that Biden’s plan could shrink the economy by 1.47 percent, reduce wages by 1.04 percent and eliminate 517,800 jobs. Yet, on the flip side, Trump’s tax cuts provided a brief sugar high to the economy, but growth didn’t rise considerably faster than in years before they were implemented. One estimate from the Dallas Federal Reserve suggests it lifted economic growth by a marginal 0.8 percent and job creation by 0.24 percentage points in 2018, the first year in which it went into effect.

The budget deficit in 2019 also widened to the largest since 2012, setting the federal government up on less-sustainable footing by the time the coronavirus pandemic rolled around.

Pandemic puts policy changes in question

Raising taxes might not be a first-day priority. The likelihood of either candidate’s proposals getting through also depends on which party occupies both chambers of Congress. A Democratic-controlled Senate and House might be less likely to push through Trump’s reductions, even if the president is reelected. Republicans might be an even tougher goalie for Biden’s tax plans if they maintain control of the Senate. That could even be true if both chambers flip their majority, though moderate-leaning Democrats or Republicans might be more likely to reject the most progressive or conservative of policies.

“Most of these provisions would ride on full Democratic control, and even then, some of them are more likely than others,” says Garrett Watson, senior policy analyst at the Tax Foundation. “Another aspect of this is seeing how strong the economy is for some of these tax increases.”

That hints at an even bigger question mark: How these proposals might work given the current crisis. Investments in infrastructure might be hard to push through if the U.S. faces a second wave of infections, a significant downside risk to the U.S. economy, according to economists. Meanwhile, raising taxes when the financial system is still in a deep economic slump might be a challenge.

With interest rates also at near-zero percent for the foreseeable future and the stock market on the rise, other experts point out that corporations might already have access to low-cost capital, either in debt markets, the stock market or from lenders they work with altogether. That might indicate there’s an economic rationale to pushing forward with targeted tax increases if it’s going to fund better, jobs-fostering initiatives.

Big companies can “pick up the phone and call their banker and negotiate a very low interest rate. Or if they’re a public company, they can float more stock,” says Seth Harris, former acting U.S. Secretary of Labor during the Obama administration who is now a policy lawyer in Washington. “There’s a lot of cash sloshing around, so the idea that what we need, more than anything else, is more cash sloshing around, has been proven false over and over again.”

Research from the U.S. Department of Agriculture suggests that every new $1 billion put toward the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) generates $1.54 billion in GDP. The Washington Center for Equitable Growth estimates that unemployment insurance (UI) has at least a 1.7 multiplier effect, meaning that for every $100 increase is $70 additional for GDP in the private sector.

A Bankrate survey from April found that individuals’ preference to save the $1,200 (or more) coronavirus stimulus checks increased with income. Individuals in lower-income categories tended to put it toward monthly bills or day-to-day essentials.

“You give it to an unemployed worker, a food-insecure worker, a middle-class family struggling to pay their bills, they will turn right around and spend that money,” Harris says. “That makes the money ricochet through the economy.”

Regardless of the direction, either candidate will be taking office at a time when hopes of a V-shaped recovery are dimming.

“Even with the wonderful rebound, there’s still a lot of work that needs to be done,” Skancke says. “Getting to work on that is going to be difficult regardless of who wins, and figuring out a way to govern from the center will be their biggest challenge, irrespective of a Republican sweep or a Democrat sweep or somewhere in between.”

Learn more:

- Here’s what a Trump or Biden presidency would mean for banking

- Biden or Trump? Plenty of young people remain undecided about who is best for their finances

- Which presidential ticket will be better for your personal finances?

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.