Downsizing to a home in a mobile home park? Beware the pitfalls

As retirement approaches, the prospect of downsizing into a new, affordable, energy-efficient manufactured home in a friendly, village-like mobile home park certainly has its appeal.

Unfortunately, the precariousness of building your future on land you don’t own could pull the financial rug out from under you just as your earning years have drawn to a close.

Is mobile home living worth the risk? Even its supporters have their reservations.

The reason: Less than 2% of mobile home parks are owned by the residents, according to Resident Owned Communities USA, or ROC USA. Unless you install a manufactured home on your private property, chances are someone — be it a mom and pop owner or, increasingly, a huge corporation — will be charging you rent to park your home on their land.

Expect depreciation

Bob Klosterman, founder of White Oaks Wealth Advisors based in Minneapolis and Longboat Key, Florida, points out that because mobile homes are considered portable personal property, or “chattel,” in most states, a new manufactured home starts depreciating from the moment of sale — much like a new car.

“Mobile homes are not known for their appreciation. If the land or lot is part of the deal and the location is attractive, that helps,” he says.

Still, the expected depreciation is not necessarily a deal breaker from a financial planning perspective.

“The carrying costs on a mobile home may be significantly less than for a single-(family) or multifamily home, which would allow the owner to draw less from their portfolio on an ongoing basis,” says Klosterman. “Down the road, that may be much more valuable than the resale value of the home.”

Mobile homes not really mobile

Also working against the homeowner is that whole “mobile” misnomer. Today’s manufactured homes may be better built, more energy-efficient and far more customizable than stick-built homes, but one thing they are not is mobile.

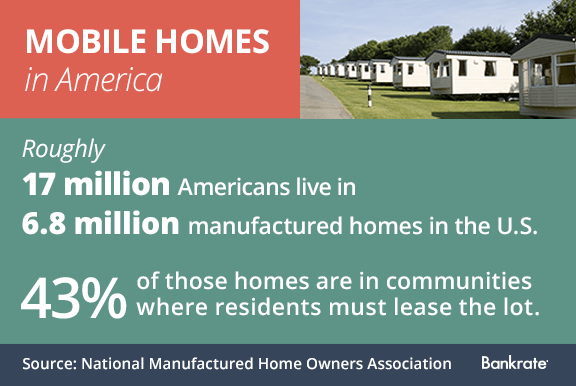

That creates a domino effect that doesn’t bode well for prospective mobile home downsizers, according to Ishbel Dickens, executive director of the National Manufactured Home Owners Association, or NMHOA, a membership organization based in Seattle.

“I call people who live in manufactured home communities prisoners in their own homes,” she says. “Many of our homeowners are paying taxes on their home at the same rate as those with a conventional home. They can’t move the home; it’s too expensive to move. Most communities won’t accept a manufactured home that’s older than a few years, so there’s nowhere to move it to. And no one wants to buy it in a community where the rents continue to go up and the homeowners have no way to address that issue.”

The zoning trap

Because many mobile home communities were originally built outside the city limits, the land beneath them is often zoned commercial rather than single-family residential.

“Eventually, that land becomes very valuable and so it’s sold to the Wal-Marts and big-box stores of the world,” says Dickens. “That’s a huge concern. You have no control over what’s going to happen to the land.”

Laws favor landlords over tenants

As the land beneath them appreciated, mobile home communities have increasingly been acquired by corporations. Tim Sheahan, NMHOA president, says the lack of substantive landlord-tenant statutes to regulate the tenuous relationship between faceless corporations and nervous mobile home owners (14 states lack any statute whatsoever, according to Sheahan) has created strong incentives for landlords to raise rents.

“Not only does it increase the owner’s monthly income, it raises the value of the community if they want to sell it. And if they raise the rents high enough, they can economically evict homeowners, capture the homes for little to nothing, and profit by reselling or renting out the homes,” he says. “Not only can residents not afford to stay in their home, they can’t sell it because no one wants a home with that high rent. In some coastal areas of California, it’s estimated that for every $100 monthly rent increase, the home values decrease by $10,000.”

Notice a common theme here? Landownership, or lack thereof, remains the fatal flaw in what could otherwise be a remarkable story of unsubsidized housing for low-income Americans.

Changing the rules

Paul Bradley hopes to change all that, 1 mobile home park at a time.

As president of Concord, New Hampshire-based ROC USA, Bradley and his team have helped residents in more than 100 mobile home parks in 14 states incorporate and collectively purchase the land beneath their homes from private community owners since 2008, with a 100% success rate — no foreclosures or business failures.

Under ROC USA’s limited equity cooperative model, homeowners still don’t own the land parcel beneath their feet; instead, they own a pro rata share in the resident corporation that owns the entire mobile home park. Still, it does solve several major downsides to mobile home living.

“Low share value co-ops are the easiest for homeowners to buy into because you don’t have to come up with big money for a share and the house trades at market value,” Bradley explains. “Because there is some contributory value to the house from the land itself, home values will improve over time.”

What is a limited equity housing cooperative?

- Each resident owns a membership interest in the corporation that owns the land.

- Residents do not directly own their own piece of land.

- Co-op membership entitles residents to a long-term lease and a vote in corporate governance.

- Co-op members are considered both lessees and owners.

- Prices for membership interest are determined by the members at a low level and remain fixed to keep the housing affordable for current and future residents.

These co-op arrangements also give homeowners control over lot rents, provide the logical solution to community upkeep, and contribute to community stability by minimizing the threat of redevelopment at the hands of profit-hungry corporate landlords.

While ROC USA usually requires a 51% majority buy-in, they’ll get the wheels moving for motivated communities with a predevelopment loan at 40% membership. What happens to those homeowners who refuse to join the co-op?

“They can remain a nonmember and continue to live there; the co-op won’t evict anybody for being a nonmember,” says Bradley. “What will happen is, over time, as those nonmembers sell their homes, the new homeowners coming in are required to become members, so they will eventually get to 100%.”

But even Bradley admits the resident-owned movement may face slow-going for the foreseeable future, in part because landlords in most states have little or no obligation to share their plans to sell or redevelop their properties with residents.

How to search for a mobile home park

Barring the likelihood that you have a resident-owned community in your area, consider these house-hunting tips:

- Locate a community owned by a nonprofit or housing authority: “Their land is secure and you know what your rent is going to be,” says Sheahan. In the case of a housing authority, “they can only charge 30% of your income for rent because they have government subsidies.”

- Look for a long-term lease: Some communities offer 5-, 10- or even 20-year leases to reassure tenants and attract new residents. “Read the lease carefully, and run it by an attorney before you sign,” Bradley says.

- Ask about a homeowners association: While some landlords forbid them, communities that give residents a voice may be the best choice.

- Ask the hard questions: What have the rent increases been for the past 5 years? What are they likely to be for the next 10? What pro rata community maintenance fees are involved?

- Get it in writing: “Don’t be taken in by the picturesque brochure,” Sheahan says.

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.

You may also like

Shopping for home insurance? Waiting until you move may cost you