‘Typosquatting’: How 1 mistyped letter could lead to ID theft

Remember when you used to think learning how to spell was a useless waste of time and cursed your teachers for making you do something that would never have any real-world benefit? Turns out you were wrong.

Missing just a few letters in a web address can cost you the money in your bank account, or start an all-out identity theft attack, because of a type of fraud called “typosquatting.”

Typo-what-ing?

Typosquatting is a type of online fraud based on the assumption that people are predictably bad at spelling.

“When you look at people who are typing in domain names, when they type them into web browsers at home, we find that with a certain regularity, people make the same typos over and over again,” says Matthew Green, an assistant research professor at the Johns Hopkins Information Security Institute in Baltimore.

That creates an opportunity for hackers.

“People anticipate that, and they try to go out and find those common misspellings, and they register them and put up copies of a bank’s website that look identical, and then they use them to get people’s credentials,” Green says. “The idea is to put out a net. You hope that some people will make some mistakes.”

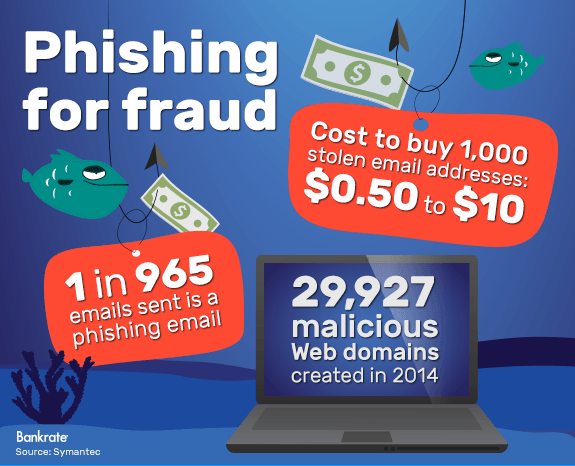

Phishing

Attempting to deceive individuals into providing sensitive information online for the purposes of committing identity theft or other types of fraud.

How typosquatting works in practice

Rajiv Motwani, director of security research at Websense Security Labs, gives an example of what a typical typosquatting attack might look like.

Say criminals wanted to target Bank of America customers. They might register “BankofAmerlca.com,” one letter off from the bank’s actual domain, and set up a fake site. (This is also known as “spoofing.”)

“The attacker puts up a page that looks very much like Bank of America’s website, so you will go ahead and enter your credentials there, thinking you are logging into the bank,” Motwani says.

From there, it’s off to the races, Green says.

“They can then log on to your banking website and transfer money and do all kinds of things,” Green says.

Spoofing

Creating a realistic copy of a website in order to trick victims into entering personal information, or for some other purpose.

Banks battle typosquatting

Typosquatting has been around for a while, so many financial institutions have taken steps to protect customers, Green says.

“Some sites now go out of their way to go lock up and register all the common, closely related domain names, and they also will monitor to see if you’re registering another one that’s too close, but not everyone does that, unfortunately,” he says.

Why not? It mostly comes down to cost.

“(Registering a web domain) only costs maybe $10 a year, but if you’re trying to lock up 50 of them, most small websites don’t have the resources to do that,” Green says.

Protect yourself

There are some actions consumers can take to protect their accounts, he says. An obvious one is, when visiting financial sites, double-check the URL before logging in.

“Be very careful entering things,” Green says. “If you’re going to PayPal or you’re going to your bank, just be very careful and pay attention to what you type.”

Another way is to make sure you’re on your bank’s real website by looking at the address bar on your browser. Next to the lock icon that should appear on any site where you’re logging in to a financial account, up-to-date versions of Internet Explorer, Mozilla Firefox and Google Chrome will have the name of the company that has registered the site, Green says.

And because customers rarely know they’ve fallen victim, it’s always a good idea to keep a close eye on your account statements so you can clue in quickly to fraudulent activity.

“They’re not going to know there’s a mistake,” Green says. “They think they went to their own bank website.”

If you think you’ve been a victim of fraud, it’s also a good idea to check your credit report for unusual activity. Get your report for free at myBankrate.

Why we ask for feedback Your feedback helps us improve our content and services. It takes less than a minute to complete.

Your responses are anonymous and will only be used for improving our website.